Have you ever noticed the odd qualification in the key statement of the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats: [W]hatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” (Matthew 25:40)(NIV) Why did Jesus qualify “the least of these” with the phrase, “brothers and sisters of mine?”

I came at the same topic from a different angle in Who are Christians to love? I raised the question, then, whether “brothers and sisters of mine” limits the people we are to care for – limiting them to brothers and sisters of Jesus. What does that phrase mean in the context of the parable of the Sheep and the Goats?

Elsewhere, Jesus tells his disciples that the world will know they are his followers by the love they have for one another. (John 13:35) When Jesus learns from someone in a crowd that his mother and brothers are looking for him, Jesus says, “[W]hoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.” (Matthew 12:50)

These verses in other contexts have prompted some scholars to conclude that we are only called to love fellow believers. They conclude that only the care we show for fellow believers who are hungry, thirsty, naked, a stranger, or a prisoner is showing care for Jesus in the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats. Some even narrow the focus further, taking the position that Jesus was only referring to his disciples (with whom he shared the parable).

This, however, is a minority view. Most of the early church fathers and theologians do not hold that view because of the many Bible passages that instruct us to love our neighbors and even our enemies. The Parable of the Good Samaritan makes this point rather clearly, as I show in the blog article linked in the opening paragraph.

In another article, I tackled the question, Why does Jesus repeatedly prioritize Christians loving one another? It seems that Jesus does prioritize our love for fellow believers. Paul also prioritizes Christian love for fellow believers when he says, “[A]s we have opportunity, let us do good to everyone, and especially to those who are of the household of faith.” (Galatians 6:10)

I note in the previous article that Jesus emphasized loving each other as he was preparing his disciples for the imminent reality of his death. In that context, he was encouraging them to stick together and to love each other. The context matters.

In other contexts, Jesus told his followers to love their neighbors and their enemies. Thus, Christian love is not exclusive to loving Christians.

Yet, Jesus does seem to prioritize love for fellow followers of Christ at some points.

Perhaps, Jesus was letting his followers (and us) know that we need to love each other, first, before we can love our neighbors (and then our enemies). If we cannot even love those who love us and think like us, how can we love our neighbors – and how in the world can we love our enemies?

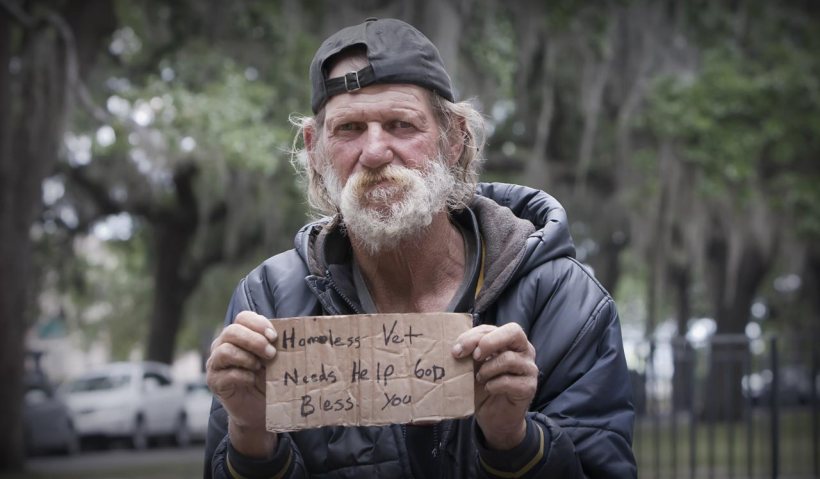

I encourage you to read the previous two blog articles if you want a more compete analysis on the subject. In this blog article, I want to explore the majority way of reading “whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” (Matthew 25:40)

Continue reading “Who Are the “Least of These?””