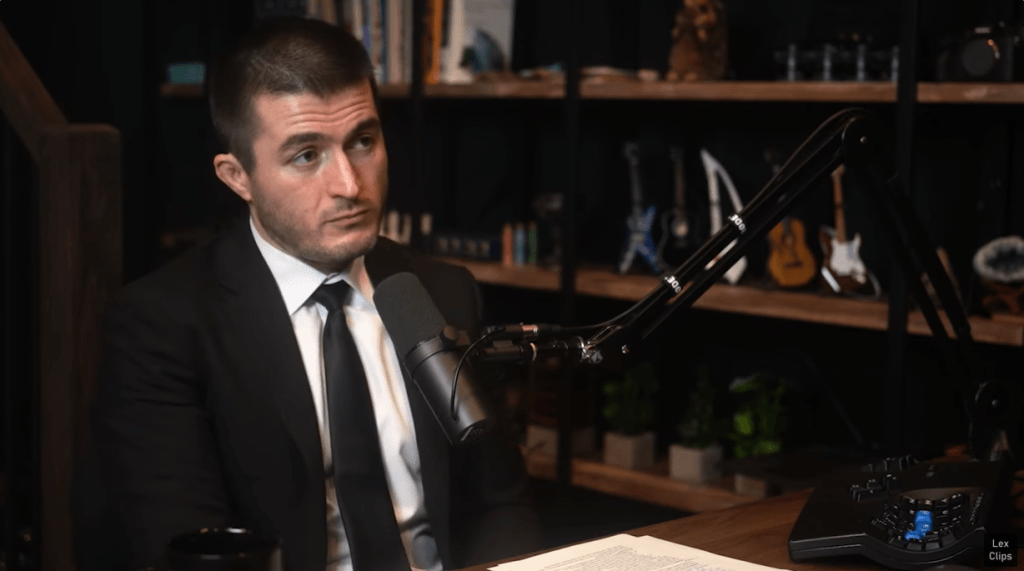

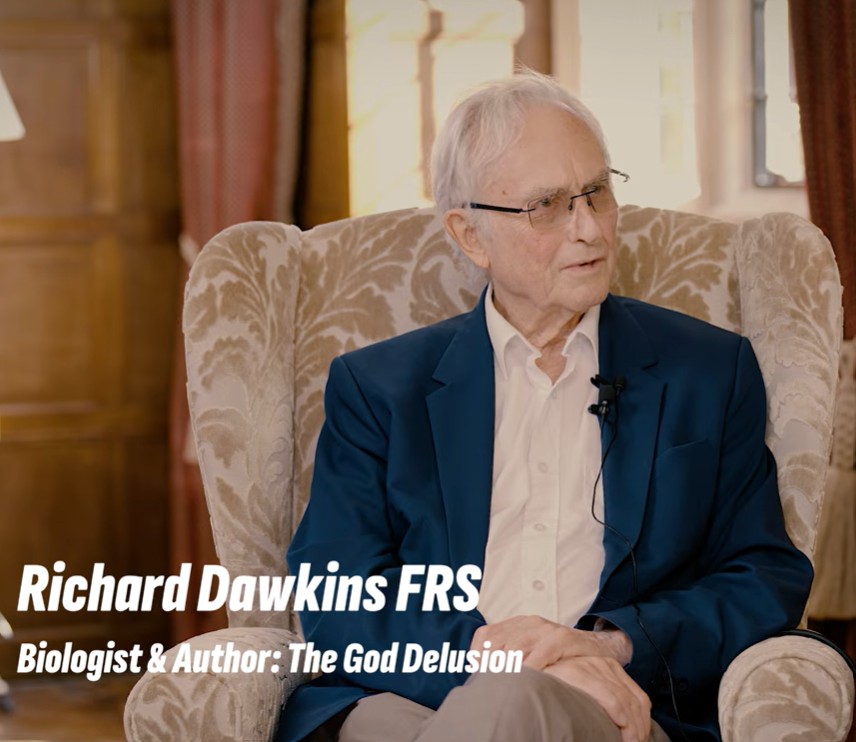

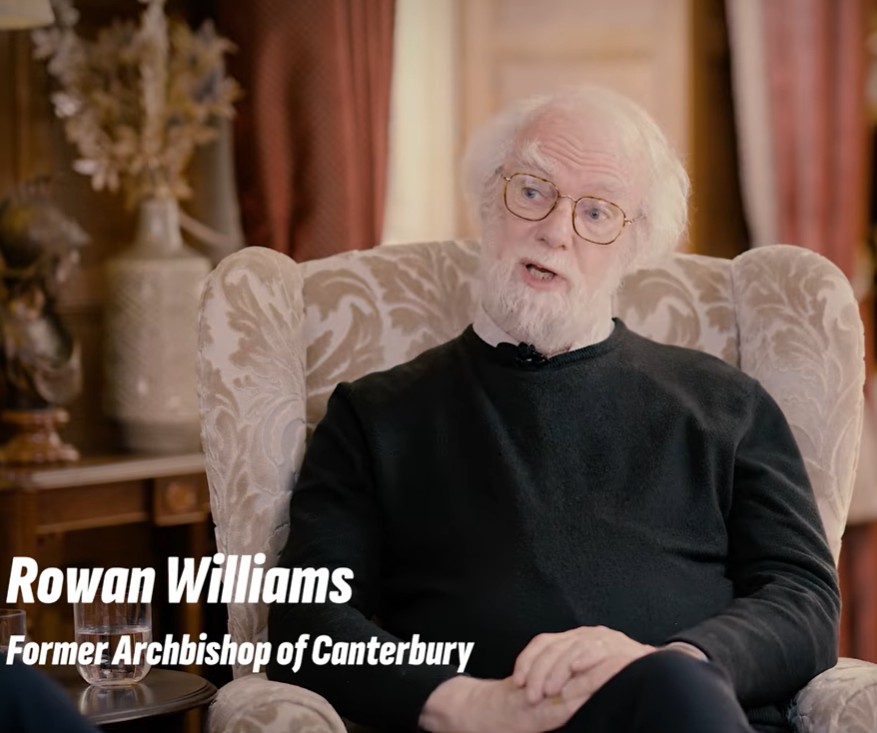

The first episode of the Uncommon Ground podcast with Justin Brierley is titled “What is Behind the Poetry of Reality?” The podcast features a conversation with Richard Dawkins and the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams. Dawkins of New Atheist fame has a purely materialist view of reality – maintaining that reality is comprised only of materials things that operate on their own without the aid of God or any immaterial thing.

The discussion is amicable and informative, if not predictable. Rowan Williams accepts the evolutionary paradigm, but believes in God – an immaterial, personal creator of the universe. They seemed to agree on the science. The only difference is that Williams believes there is a God behind the science and the universe.

When Brierley asked Williams to summarize Richard Dawkins’ view of reality, Dawkins graciously conceded, “Rowan… understands so well that he can summarize what I think better than I can.”

Dawkins should be given credit for reading Williams’ recent book that was the backdrop for the discussion, but Dawkins admitted to being “baffled” by it.

Dawkins was unable to provide a cogent summary of Williams’ view of reality. He succeeded only in criticizing Rowan’s view, and Dawkins conceded, “I think Rowan understands where I’m coming from much better than I understand where he’s coming from.”

This reminds me of C.S. Lewis, who says that the Christian worldview can take in science into account, but a view of the world limited to the constructs of science cannot take into account Christianity. One is robust enough to hold the other, but the other is not sufficiently robust to do the same. (I have provided the whole quotation in its context below.)

I will admit that the robustness of Christianity to be able to make sense of science does not necessarily make it true. Conversely, the limited scope of science that is unable to account for Christianity does not necessarily make it untrue. If reality truly consists of nothing but matter and natural processes, then the limitations of science are the limitations of reality itself.

I think that reality is not sufficiently explained by science, which is limited to natural explanations. I am also fascinated with Dawkins’ attempt to explain his own worldview as follows:

“I see the world as a very complex thing, like a clock or like a car or like a computer, and, and in the case of a clock or a computer or a car, I know how it’s made. It’s made by engineers with drawing boards and they… put together the parts and, and those parts all work together. [T]he equivalent of the engineer in the world of nature is evolution by natural selection.”

I am an English literature major and an attorney. In both disciplines, the ability to draw connections, and distinctions, and juxtapositions between and among word meanings and concepts is essential. Attorneys are professionals in comparing and contrasting facts and circumstances to be to argue (consistent with clients’ interests) that laws either apply in the same way or do not apply in the same way to similar but different sets of facts and circumstances. Perhaps, this why I noticed that Richard Dawkins made a category error. Or did he?

Continue reading “Making Sense of Science and Theism: Evolution, Engineers, and Category Errors”