I was listening to the podcast, Apollos Watered hosted by Travis Michael Fleming, recently when NT Wright made a very simple, but poignant, statement:

“One of the most fundamental things about Christianity is that it is for everyone.”

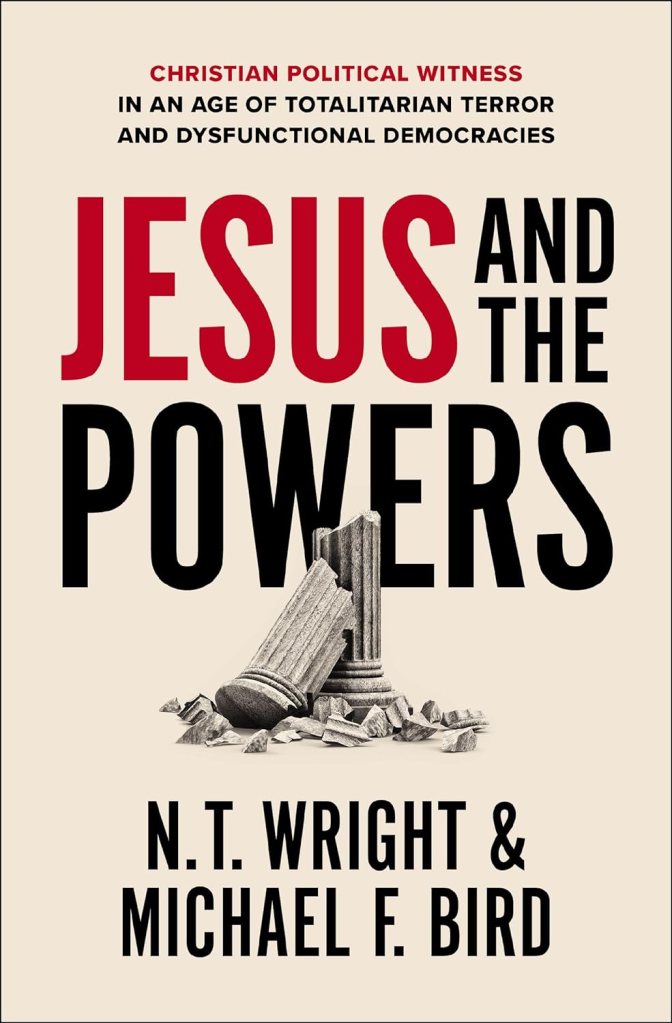

NT Wright, of course, is from the UK. He just authored and published a book with Michael F. Bird, that is called JESUS AND THE POWERS, Christian Political Witness in an Age of Totalitarian Terror & Dysfunctional Democracies.

The context in which he made this comment was a discussion on Christian nationalism. Christian nationalism is currently a hot topic in the United States, though we are hardly the first nation that has religious, nationalist tendencies. England had such a period in its history.

The nation of Israel had arguably the most provenance to think that way. After all, Israel was a nation of “God’s chosen people”. God became incarnate in Jesus in the 1st Century, and He “came to His own” – His chosen people. Before moving on to the point I am inspired to write about today, I want to focus on how God’s chosen people reacted to God becoming flesh and walking among them.

The Apostle, John, tells us in the first chapter of his Gospel that they, tragically, “did not receive him!” (John 1:1-11) They did not recognize God who had become flesh and was standing right in front of them!

That stunning fact should cause us to ask, “Why?” How is it that God became flesh, and He walked among the very people He chose, and they didn’t recognize Him?

We might excuse them on the basis that we have the Holy Spirit, and they didn’t. We might be tempted to think that we would respond differently today because of that advantage. But then again, they had God in human flesh!

We might assume that having the Holy Spirit makes us different than them. Perhaps, that is true. Theoretically, a person who actually has the Holy Spirit and who actually lives by and listens to the Holy Spirit does seem to have advantage.

Of those who have the Holy Spirit, do we actually live by and listen to the Holy Spirit? All of the time? Even most of the time? I can’t answer that question for you, but I think it is a question worth asking ourselves.

NT Wright is a prolific and influential theologian. He has written key works on Paul and Romans. His insights are particularly relevant and poignant as such an expert who has no dog in the political and cultural “war” that rages in the United States of America.

Such a simple statement: “Christianity is for everyone.” Who would not agree with that statement? Jesus said he came for everyone who believes. Paul said there is no Jew nor Gentile; and we are all one in Christ.

In the 1st Century Jewish world, only two groups of people existed: Jews and everyone else. The Jews called everyone else Gentiles. What Paul means, therefore, is that everyone in the world is unified in Jesus Christ. This should be our reality as Christians, right?

Paul said that Jesus tore down the wall that divided the two groups of people in the world, and he made the two groups one. He reconciled all people to himself through the cross. (Ephesians 2:14-16)

The danger of Christian nationalism in the United States (or anywhere) is that some Christians may see themselves as uniquely Christian, uniquely privileged by God, and they may conclude that their own nation that they consider to be Christian is uniquely, divinely authorized by God. That attitude can lead to us to see other people as less uniquely blessed and less divinely privileged.

This is dangerous because we are tempted to view ourselves as better than others. We may even excuse some of our ungodly behavior because we are a Christian nation that has divine authority in the world.

This attitude can hinder us from seeing our own faults and weaknesses that are unique to our culture. We are apt not to see the planks in our own eyes while we focus our attention on the specs in others’ eyes, assuming ourselves to be better than others.

We might also tend to focus on maintaining our privileged position we believe God has given us to the exclusion of other people. We might be tempted to focus on our own good while we should be focusing on helping our neighbors, including our foreign neighbors – and even our enemies.

Jewish people in the 1st Century had this kind of attitude, and it blinded them from seeing who Jesus was – the Messiah they had been waiting for – because they thought he was only their Messiah, and he would liberate only them. They weren’t prepared for a Messiah who came to liberate the whole world!

Though “God’s own” didn’t receive Him, “Yet to all who did receive him, to those who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of God….” (John 1:12) We might be so familiar with the following verse that we miss the scope of God’s focus:

“For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him.”

John 3:16-17

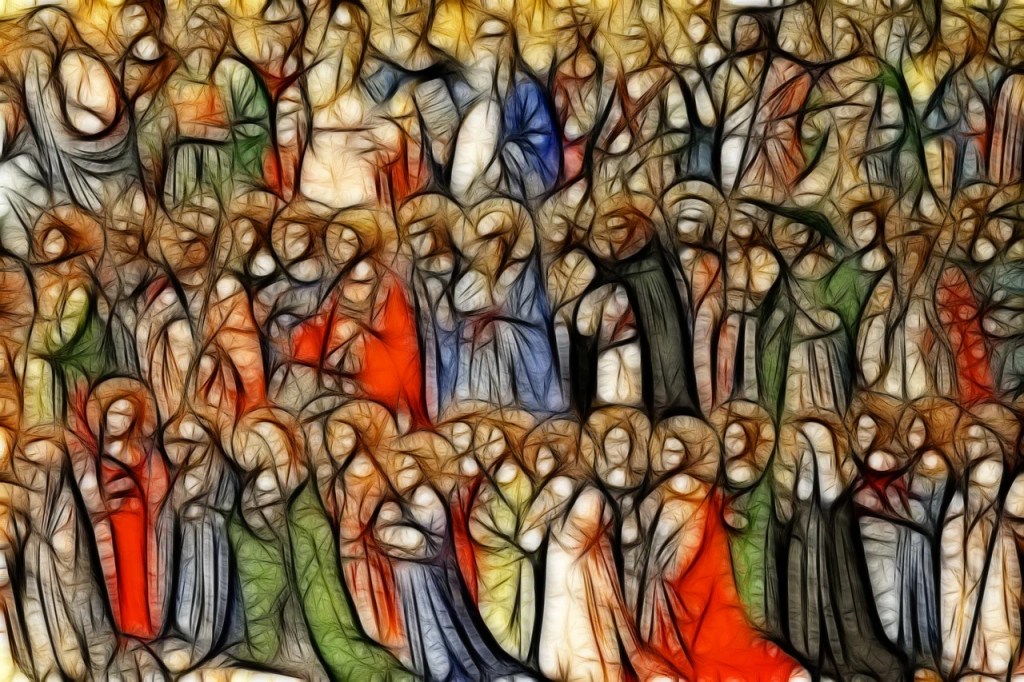

God’s focus is the world – the whole world. He even gives us a sneak peak at His end game through the same Apostle, John:

“After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb.”

Revelation 7:9

With Christian nationalism, however we might define it, our perspective is too narrow. The danger is that we focus too much on us when God is focused on the world.

Religious people wanted to kill Jesus in his hometown because he challenged their views as God’s privileged people. They became angry with Jesus when he talked about Elijah visiting and blessing the Canaanite woman in Sidon to the exclusion of all the widows in Israel. They were enraged when Jesus said that Elisha healed the Samaritan war general of leprosy rather than people in Israel who had leprosy. They were so incensed by Jesus pointing these things out that they tried to throw him off a cliff! (Luke 4:24-29)

Christian nationalism of any kind flirts with unhealthy pride in national identity. Pride and identity associated with anything other than Christ has a tendency to warp us inwardly and to diminish our sense of primary identity in Christ. Thus, Christian nationalism can lead us to diminish our love for God, as well as our love for our neighbors.

When we think too highly of ourselves, we value our own culture and ways of looking at and doing things more than we should. When we think too highly of ourselves and value our own ways too much, we also tend to devalue others and the ways of other people. Thus, Christian nationalism can lead us to diminish our love for others.

As finite human beings, we all have a deficiency of perspective. Each individual and cultural perspective is limited, which is why Isaiah said:

“For my thoughts are not your thoughts,

Isaiah 55:8-9

neither are your ways my ways, declares the Lord.

For as the heavens are higher than the earth,

so are my ways higher than your ways

and my thoughts than your thoughts.”

In short, we do not have the perspective of God. His perspective is far greater than ours. This is true individually, of course, but it’s also true of humankind. It is equally true of people groups, cultures, and nations.

Continue reading “The Problem with Christian Nationalism”