I went to bed last night concerned I was getting things wrong. Specifically, I have been critical of Donald Trump and what he has done since he took office again, and I have been getting push back from many people. It isn’t the many people that concerns me, but my brothers and sisters in Christ who are calling me out on this.

It seems so obvious to me that the things being done are wrong, and the way they are being done is wrong, but other Christians are not seeing it. I prayed to God last night, “If I am wrong, please correct me.”

This morning my daily reading included this verse:

“I am sending you out like sheep among wolves. Therefore be as shrewd as snakes and as innocent as doves.” Matthew 10:16

I was doubting myself last night, so my first thought was to check the context, even though I know it. Sure enough, it was what I remembered:

“These twelve Jesus sent out with the following instructions: ‘Do not go among the Gentiles or enter any town of the Samaritans. Go rather to the lost sheep of Israel. ‘” Matthew 10:5-6

I have read this passage dozens of times, probably, since I became a Christian over 40 years, but I didn’t realize the context of the sheep among wolves statement made by Jesus until the last year. When I read that passage recently, I said to myself, “Wait a minute! Jesus said that to his disciples when he sent them out to his own people – the Jews.” What!?

He said, don’t go to the Gentiles, and don’t even go to the Samaritans; go “the lost sheep of Israel.” He would later send them to the Samaritans; and he ultimately sent his followers to Judea, to Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.

Of course, he sent them to the lost of sheep of Israel. Maybe not all the people of Israel were lost sheep. Maybe the wolves were only among the lost sheep of Israel.

Surely, the people in the church today are not the lost sheep. The church is filled with the elect. The church is filled with sheep who hear the shepherd’s voice. I believe that is true!

At the same time, I think it is safe to say that not everyone who goes to church is a child of God. The old adage that parking yourself in a garage does make you an automobile is true. Jesus said it this way: “The kingdom of heaven is like a man who sowed good seed in his field. But while everyone was sleeping, his enemy came and sowed weeds among the wheat….” (Matthew 13:24-25)

I am sobered by this. I don’t think that Jesus was saying that all God’s people at that time were wolves. Maybe the wolves weren’t even people. Sometimes, we can take a metaphor too far. He was telling them to be careful, to be circumspect, to remember what he taught them, and not to be lead astray – even among God’s people. We may be sometimes fooled into listening to the voices of wolves, rather than the voice of the Good Shepherd.

This is the story of God and His people. God sent His prophets to His people again and again, and they did not listen. (Jeremiah 26:5) When God commissioned Isaiah, He told Isaiah that the people would hear, but not understand, and they would see, but they would not perceive, and this would continue until the land was in ruins and only a remnant remained. (Isaiah 6:1-13)

Of course, I am not the Prophet, Isaiah. I am a sinful man saved by the grace of a loving God. I have my own faults and biases and sinful tendencies, and I could be wrong. I am acutely aware of this.

Last night before I went to bed, I listened to a pastor talk about the triumphal entry in Luke, and I remember it this morning. I wrote about the triumphal entry last year with some new insights I had gained from a podcast. He hit on the same insights.

Jesus was entered Jerusalem on the colt of a donkey around the time Pontius Pilate entered Jerusalem from the opposite direction, from Caesarea. Picture the incongruity of a full grown man sitting on a colt of a donkey with his legs dragging the ground under the poor little beast. Then picture the Roman ruler of the land came from the opposite direction in a mighty procession with banners and fanfare and a show of force with all the military show of Communist China.

Jesus was coming to die on a cross, but the people greeted him like he was a king who would ascend the throne of David and overthrow the Roman government. They shouted, “Hosanna!” (Save us!) They waived palm branches to herald the Messiah they believed would save them from the Romans like a hammer, and they laid their garments down in submission.

The people didn’t understand that Jesus came to die on a cross. The poignancy of this incongruence is understood best by how the story in Luke ends:

“As he approached Jerusalem and saw the city, he wept over it and said, ‘If you, even you, had only known on this day what would bring you peace—but now it is hidden from your eyes. The days will come upon you when your enemies will build an embankment against you and encircle you and hem you in on every side. They will dash you to the ground, you and the children within your walls. They will not leave one stone on another, because you did not recognize the time of God’s coming to you.'”

Luke 19:41-44

Those people would have said they did recognize the time of God’s coming, right?! They got it right: he was the Messiah! They recognized that Jesus was God’s Messiah promised of old.

In that general sense, they did get it right. Jesus was/is the Messiah, but their expectations of what that meant and what he would do was wrong. They thought he came to conquer, but he came to die.

By the end of that week, the people who waived palm branches and laid their garments down had changed their tune. They wanted Barabbas released, not Jesus.

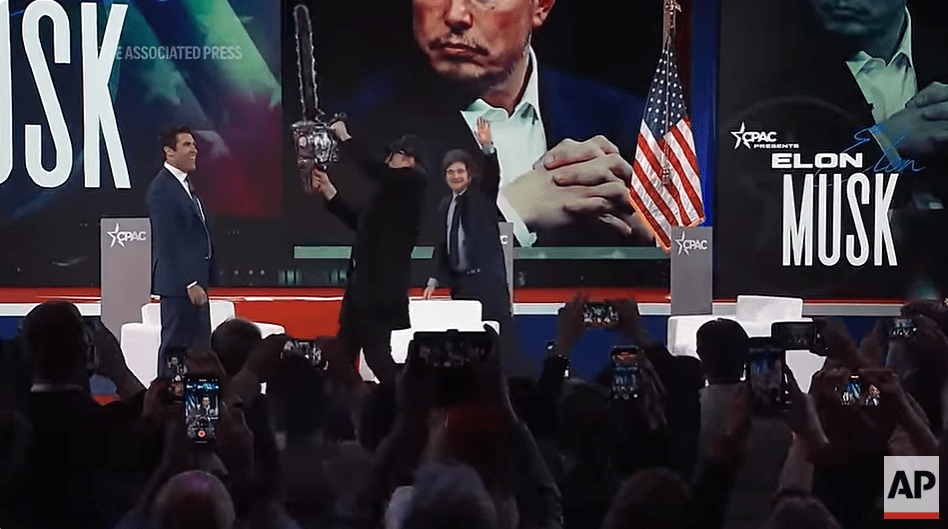

As discussed in the conversation linked below in the video, they wanted the way of Barabbas – the sword – not the way of Jesus, the cross. They didn’t want a suffering Messiah; they wanted a conquering Messiah. They didn’t want the Lamb of God; they wanted the Lion of Judah.

We aren’t much different than they. For all of our Bibles and bible apps, we don’t even know Scripture as well as they did! Lifeway Research reports that only 36% of Evangelicals read the Bible every day, and only 32% of Protestant, read the Bible every day.

We have our own expectations of the way God should do things, and we tend to lean back into what someone recently called the default stance of the flesh – the appeal of power and influence. But, that isn’t God’s way. Jesus showed us God’s way, and he invites us to follow his way as he followed the Father’s way in this present world.

Paul reminds us,

“But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things—and the things that are not—to nullify the things that are….”

1 Corinthians 1:27-28

We need to be careful not to be hearers who don’t understand and seers who don’t perceive. We need to be careful to choose God’s way, which is not our way. We need to carry our crosses and not swords.

Does any of this make me “right”? No. But, I am seeking God. I am trying to be true, to know Him, and to be like Him. That is my heart’s desire. I am trying to recognize and honor God in these times and to reflect His heart and character as best as I can understand it.

The lesson of the words of Jesus to be careful of the wolves among the sheep, the lesson of the prophets, and Paul’s reminder that God shames the wise and the strong by choosing what seems to be foolishness and weakness means that I need to resist the default position of the flesh (to rely on power and influence). I need to be grounded in God’s Word and not everything that anyone who is a Christian says. I need to be aware that weeds grow among the wheat and wolfish things appear among the sheep.

Though every man be a liar, yet God is true! (Romans 3:4) The heart of a man is deceitful above all things. (Jeremiah 17:9) This is true of me and my heart if I am not careful and do no guard it. We need each other, and we need to hold each other accountable, not to political ideologies and cultural ways, but to the Word of God and the way of Jesus.