I have heard many people say that they would believe in God if God revealed Himself to them in clear, undeniable ways. Richard Dawkins, the New Atheist, said that God would have to write a direct message in the sky before he would believe (and then, he added, he would still assume that he was hallucinating or something else before believing it).

Young children tend to believe in God innately. This is true whether children are raised in religious homes or non-religious ones and in countries that are predominantly religious and in countries that are not. Even atheist sociologists have observed this phenomenon that some people have called “universal design intuition.” (See Universal Design Intuition & Darwin’s Blind Spot)

Since the Enlightenment, the general assumption in scientific and academic circles is that children outgrow naïve faith and civilizations do too as they advance in knowledge and sophistication. Thus, the modern assumption is that we outgrow faith in God as people and societies mature.

There is some truth to that assumption as we can see anecdotally (maybe in your own life or in the lives of people you know) and from the history of Western Civilization, with evidence of declining religious belief. Still, 81% of people in the United States in 2022 believed in God (or a higher power) (as reported in a Gallup poll), and the number increased to 82% in 2023 (according to a Pew Research poll).

We have all heard about the “Great Dechurching” – the 40 million Americans who used to go to church, but no longer do. We have also heard about “the rise of the nones“, the increase in the number of Americans who are atheist, agnostic or religiously unaffiliated, which increased precipitously from 16% in 2007 to 30% by 2022!

The nones include people of every age, but the highest percentage of nones are Gen Z and millennials. These age groups have largely grown up not going to church, yet, Bible sales surged in 2024 by 22% (after years of declining sales), and that surge is attributable to first time purchasers among Gen Z and Millennials. (See Bible boom: Why are people buying so many Bibles?; and US Bible Sales Jump 22% in 2024, Driven by First-Time Buyers and New Versions: Circana BookScan)

The hint of a spiritual renewal in the West isn’t limited to young Americans. Justin Brierley has reported on and written a book about the Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God in the UK. (See The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God: Why New Atheism Grew Old and Secular Thinkers Are Considering Christianity Again) Agnositics and atheists, at least in the UK, are rethinking their positions on Christianity in noticeable numbers.

While Brierley’s thesis is largely based on anecdotal evidence, the volume of his anecdotal evidence is impressive. He has been hosting dialogues between atheists and Christians regularly since the mid-2000’s, and his data comes from a combination of atheists who have recently cozied up to the idea of God and religion and former atheists who unabashedly believe in God now.

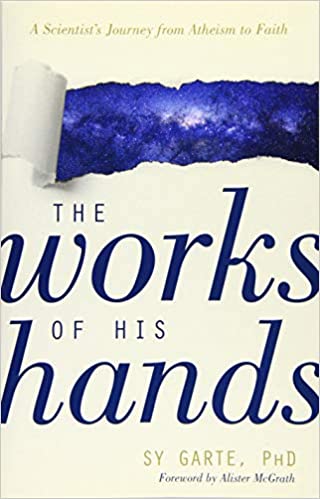

My writing today is inspired by one such former atheist, a bio-chemist with a robust career in science, who became a believer in his middle age. Sy Garte wrote a book about his journey from atheism to faith, The Works of His Hands: A Scientist’s Journey from Atheism to Faith, in which he explains how a combination of science and his experience led him to believe.

The science opened his mind to the possibility of God. His study of religions, philosophy, and theology led him to an intellectual acknowledgement of the likelihood of God, but his experience and willingness to embrace it brought him in the door to faith in God.

In a recent interview with John Dickson on the Undeceptions podcast, Sy Garte provides some advice to listeners who believe science holds all the answers to reality and truth by insisting that nothing in science contradicts the Bible.

If you read his whole story, he explains how science suggested the possibility of God to him, but he also emphasizes the importance of experience in belief. His acknowledgement of the role of experience, I think, is important, and it is underappreciated.

Skeptics and believers, alike, discount experience. A skeptic might chalk experience up to fantasy, a desire to believe, a disconnection with reality, or similar thinking. A believer might question the experiences of people who arrive at unorthodox beliefs based on their experiences.

Clearly, experience must be tempered by facts, science, and sound reasoning, but Sy Garte maintains that experience is good evidence, nevertheless, primarily for the one who has the experience. In doing so, he acknowledges the objection by the person who hasn’t had such an experience, and his response to the person who hasn’t had an experience with God is what I want to focus on today.

Continue reading “Why Doesn’t God Reveal Himself to Me?”