I have been meditating on the hiddenness of God lately and leaning into the mystery of God’s hiddenness. I am intrigued by it. The Bible is forthright about the hiddenness of God.

As I think about the hiddenness of God, the mind of the skeptic plays in my ear: “How do you know God exists? Why does God seem hidden? Maybe it’s because He doesn’t exist!” Believing in a “hidden” God is belief without evidence; it’s belief in the teeth of the evidence (as Dawkins says).

My response is that we all have faith in our basic assumptions about reality. The scientist assumes only matter and motion. He sees evidence for things like gravity and neutrinos, and dark matter and dark energy that cannot be seen. The scientist reasons to the best explanation for the things that cannot be seen in order to make sense of the reality in the world, and he does so within the “limitations” of materiality.

Science, after all, is the study of the material world. That is is the scope of science as it is defined in the modern world. Science is based on what is quantifiable, measurable, observable, and reproducible.

When I do theology or philosophy, I also start with assumptions. I start with an assumption, or a theory if you like, that God exists. The proof of God, however, is necessarily different than scientific proof.

God is not a substance in the universe to be quantified, measured, observed, or reproduced in the way we can study the natural world. He is not a component of the universe. He is not comprised of matter and motion like the universe. God is not a principle of physics that can be observed in its regularity and tested by its regularity.

If God exists and created the universe, He is separate and apart from the universe. That does not mean that God is not present in some way; it means that He is not present in the same way that you and I are present. Rather, God is transcendent. He is imminent (near in some way), but not contained within the creation.

God also must have agency to have determined to create. We understand the necessity for agency by our own agency. This makes sense of the question: why is there a universe; why is there something, rather than nothing.

For the life of me, I can make no sense of the assertion that a universe can create itself. What kind of voodoo magic is that? That conclusion is based on an assumption that matter and motion is all that exists, but we cannot prove that assumption.

To say that God must have agency is not to be anthropomorphic about it but to reason to the best explanation based upon what we know, which is our own agency and the way we conduct ourselves in the world. Where does a universe come from? The simple answer is that it comes from a creator who has agency, who has intentionality, and the ability to will and to act according to His purpose and design.

Where does intricate, fine-tuned complexity that is complex to the nth degree come from? It comes from a mind, from a creator who conceives a plan and then implements it. We know that from the way human beings create things. Where did we get that capacity? Like things produce or reproduce like things.

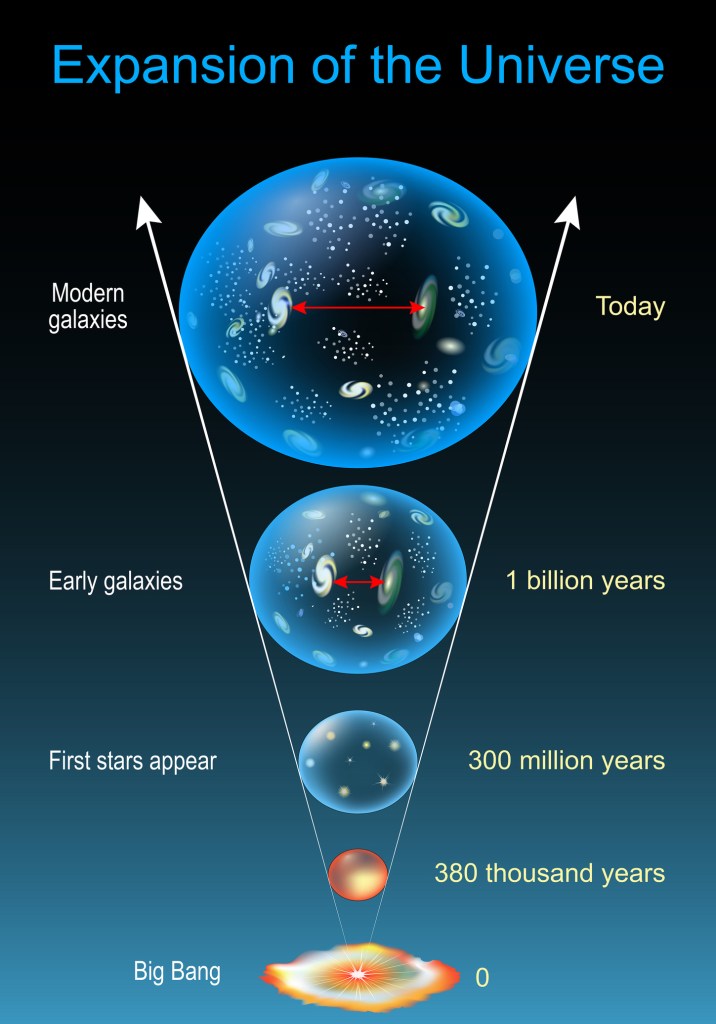

We know that the universe is “winding down”. That is what the law of thermodynamics tell us. Entropy is the rule. This means the universe is not getting more complex; it is breaking down, evening out, cooling, and becoming less complex over time.

Over course, this is occurring over a very, very long period of eons, so (perhaps) there is enough energy in the universe for complexity to form in areas of the universe even while entropy is working its very long way toward the inevitable heat death of the universe as a whole.

Maybe, but where did the energy come from to cause the so-called Big Bang? What triggered the universe to begin to begin with?

No one can explain that who doesn’t believe in a “Big Banger”, a Creator. It is the best explanation that we have. It makes the most sense of the reality that the Universe had a beginning.

The multiverse doesn’t solve the “problem” of a beginning. It just kicks the can back down the road further. What triggered the multiverse into being? It’s an endless regression.

The Christian (Jewish and Muslim) conception of God is that God is the timeless, eternal being who always existed and was never created who chose to trigger the universe (or multiverse) into existence.

This, frankly, makes much more sense than a past eternal, non-sentient universe that just poofed life into existence. How do you get life from nonliving matter? What animates that matter?

But the questions don’t stop there. What triggers consciousness from inert, non-conscious matter? How do the fundamental “building blocks” of matter develop consciousness? It’s a complete mystery, and there is no mechanism known to modern science to explain it – other than the brute fact that human beings and (to some lesser degree) animals (and maybe plants) are conscious beings.

Consciousness is proven by the sheer fact that we are conscious of ourselves. It seems to “reside” in or be attached to the brain, but the brain by itself is not consciousness. The brain is a perfect, intricate receptacle for consciousness, but the brain and consciousness are not perfectly coexistent. They are not the same things, and science has no adequate explanation for that.

Because these things suggest looking outside the limitations of the material world for our answers, we have theology and philosophy, which can be “scientific” loosely in method and approach, but defies the limitations of scientific inquiry.

That doesn’t mean that theology and philosophy should be divorced from science (or that science should be divorced from theology and philosophy). All reality must ultimately cohere harmoniously, or we cannot call it reality.

But, I have digressed (only slightly) from the point, which is the mystery of the hiddenness of God.

Continue reading “Unveiling the Mystery of the Hiddenness of God”