The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy is just a little older than my Christian faith. It was relatively new when I first read the Bible in college and when I first asked Jesus to be the Lord and Savior of my life. I have wrestled with the idea of inerrancy from the beginning of my Christian life until now.

It isn’t that I don’t think the Bible is the “word of God”. It isn’t that I don’t have a “high” view of the reliability, integrity, and divine nature of the Bible. It isn’t that I don’t think the Bible was inspired by God and should be relied on as His word to us to follow.

I believe all these things, but I have issues with statements on inerrancy that seem to push what the Bible says about itself beyond what it says.

Finally, I have found some similar thinking in two of the great Christian thinkers of our time: Mike Licona and William Lane Craig. In his blog, Risen Jesus, Licona introduces a paper to the world that he wrote and presented at the annual meeting of the Evangelical Theological society.

In the paper, Licona cites Craig in support of a new proposal on inerrancy. First, though, he explains some of what is problematic with the Chicago Statement. I am not going to restate the points he makes here. You can read the paper, CSBI Needs a Facelift, yourself, but I will summarize it for those who don’t have the time or inclination to read the original (though it isn’t long).

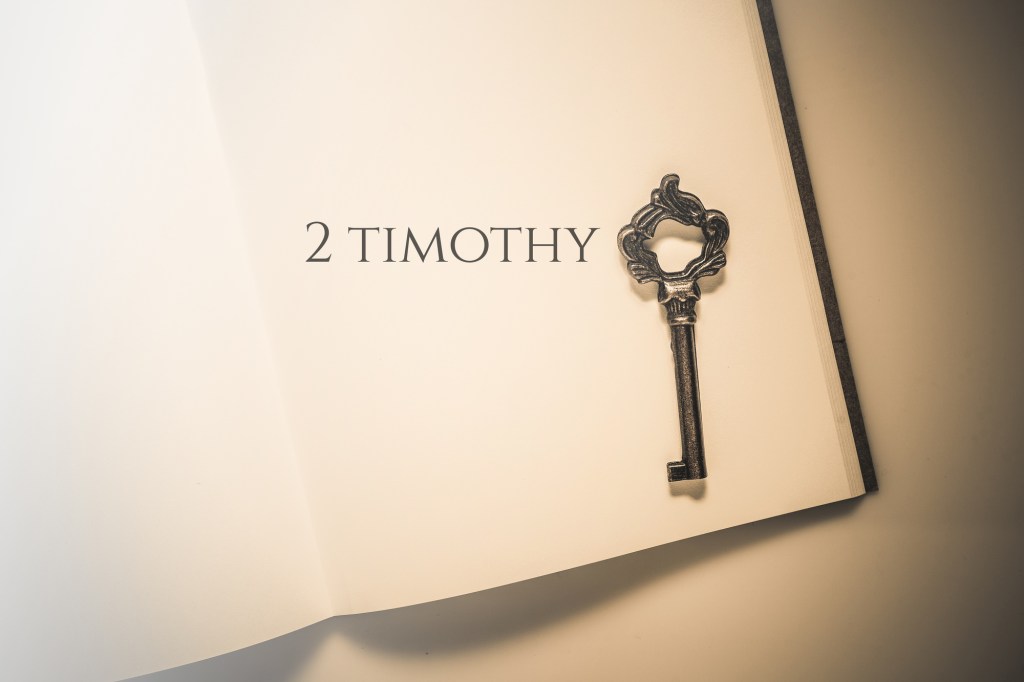

Licona starts with the two main verses that provide the inspiration (pun intended) for the doctrine of inerrancy: 2 Timothy 3:16 and 2 Peter 1:20-21. At the center of this are the words “God-inspired” or “God-breathed” which are English translations of the Greek word, “theopneustos“.

Licona traces the history of the use of the word, theopneustos, prior to the 3rd Century. The word was not often used, and it was used in very diverse contexts. Licona quotes a commentary on 2 Timothy, stating, “Theopneustos does not have enough precision to go beyond the basic idea that the Scriptures came from God.” and he concludes:

Therefore, 2 Timothy 3:16 does not contribute as much to our discussion as we may have first thought. So we should be cautious not to read more into it than Paul may have intended.

The 2 Peter 1:20-21 text speaks of prophets who were “carried along by the Holy Spirit.” Licona observes that the Greek word translated “carried along”, pherō, is also used by Philo “to describe how prophets received revelation from God, during which time they had ‘no power of apprehension’ while God made ‘full use of their organs of speech.’ Josephus likewise used this word to say that “God’s Spirit put the words in the mouths of the prophets” (quoting Licona, who paraphrased Josephus).

The 2 Timothy passage and the 2 Peter passage express different ideas and give rise to different pictures of how God speaks to/through people who authorized the writings of the Bible. some writings purport to be prophetic and some do not expressly adopt that attitude. The Chicago Statement assumes that both passages mean the same thing, but most biblical scholars disagree with that conclusion.

Licona goes on to summarize some phenomena in the text of the Bible that suggest a “human element in Scripture”. Licona concludes from this, “Although [the human element] does not challenge the doctrine of the inspiration of Scripture, it does challenge the concept of inspiration imagined by [the Chicago Statement].”

These issues with the ambiguous meaning of the Greek words and the very different images of God working to convey His “Word” through people (God-breathed and carried along by the Spirit), can be reconciled with a “new” paradigm, says Licona. This paradigm was suggested by Craig in 1999.

Continue reading “A Facelift Proposed on the Doctrine of Inerrancy”