I am writing today about the Parable of the Good Samaritan and the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats in light of the Old Testament passage that introduces what Jesus called the second greatest commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. (Leviticus 19:18) If you have read anything I have written lately, you know that I have have been meditating on this theme.

How People Misinterpreted “Neighbor”

When Jesus encountered a First Century expert in the Law, the issue became: Who is my neighbor? The Parable of the Good Samaritan was the response from Jesus. The backstory to the Parable of the Good Samaritan reveals how First Century Jews misread Leviticus 19:18 to limit who they considered neighbors. It reads as follows:

“Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people, but love your neighbor as yourself. I am the Lord.“

Just 16 verses later (in Leviticus 19:34), Moses hints at a broader, more expansive meaning to the rule to “love your neighbor as yourself”:

“The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the LORD your God.”

Distinguishing Among Jews and Gentiles

In the time of Jesus, Jews distinguished between Abraham’s descendants and everyone else (Gentiles). They limited neighbors they were instructed to love to those from among their people because they interpreted Leviticus 19:34 in light of Leviticus 19:18. They interpreted “from among the people” to include descendants of Abraham, and they likely included those foreigners who lived among them and observed their religious practices, but they did not go further.

The Hebrew word translated “foreigner” in verse 34 is ger. It generally means “sojourner, stranger, foreigner, alien,” and it literally means “a guest.” (See Biblehub) Ger is derivative of guwr, which means “to sojourn, dwell, reside, live as a foreigner,” with connotations of being a guest, shrinking & fearing, and being afraid.

According to the topical Lexicon, gurw centers on “the act of taking up residence as a non-native, a ‘sojourning’ that is self-conscious of impermanence and dependence on the goodwill of the host community.” The sense of this word as scholars have come to understand it is of foreign guests who dwell permanently among the people and conform to the requitements of the Mosaic Law. I believe First Century Jews would have had a similar understanding of the concept of neighbor that defined who they were to love.

By the First Century, there were two categories of people: Jews and Gentiles. We know from historical records that some Gentiles lived harmoniously with Jews and more or less subscribed to Jewish religious customs as they were allowed to engage with them.

The Samaritans as Others

There were varying degrees to which Gentiles could be incorporated into Jewish community. Some Gentiles were circumcised, converted to Judaism, and were fully integrated into Jewish community. The largest group of Gentiles who lived among the Jewish community, however, were the “God-fearers”. They were welcome in the temple and synagogue. They participated in prayer and instruction. They ethically aligned with Jewish community, but they were not circumcised, not bound to the full Torah, and were not considered covenant members of the Jewish community.

These Gentiles who believed in God as the Jews did, who worshipped God as the Jews did, and who lived in harmony with biblical, ethical requirements were accepted in Jewish community. They more or less represented the ger in Leviticus 19. They, like the ger, were considered neighbors who must be loved.

The question posed by the expert in the Law in Luke 10 reveals that the scope of who is a neighbor was limited, but with some sense of uncertainty, in the First Century. That uncertainty was settled by Jesus in sharing the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

Samaritans and Jews Opposed Each Other

Samaritans were ethnically Hebrew. They descended from the northern tribes of Israel. They were descendants of Abraham, but they were deviant, ritually impure, and estranged from First Century Jews.

They were people who remained in the land after the exile to Babylon and integrated with the conquering Assyrians. They opposed the return of the exiles who rebuilt the Temple. They rejected Temple worship. They rejected the Levitical priesthood returning from Babylon, and they had their own religious practices.

The hostility between the Jews and the Samaritans was mutual. They were closely related by kinship, but they disagreed sharply over theology, religious practice, and heritage. They were estranged, avoided each other avoidance, and clashed (sometimes violently).

Insiders and Outsiders

Though the Jews would accept the Gentile converts and God-fearing Gentiles into Jewish community, Samaritans and other Gentiles were excluded. They were the people the legal expert’s question was about: Who is my neighbor? They were not from “among the people.”

Many people in the Jewish community, like the expert in the law, had a theology that excluded Samaritans and most Gentiles from the definition of “neighbor”. Their mistaken interpretation and bad theology created insiders and outsiders.

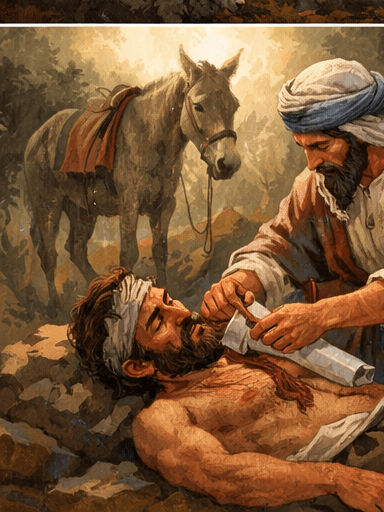

Jesus Cuts Against Our Insider Logic

Jesus reveals how God’s Word cuts against our insider logic. Jesus interprets Scripture and compels us to view our neighbors (whom we should love as ourselves) Expansively. Our neighbors include people who are not like us, people who are heretical and (therefore) threatening to us and people in opposition to us. Outsiders.

Jesus shockingly made a Samaritan the hero in the Parable. Most Jews would not have used “good” in the same sentence as a Samaritan. Samaritans were outsiders, people in opposition to the Jews, heretics, and estranged. Samaritans were not seen as neighbors, but Jesus disavowed them of their bad theology.

We know this, but we are not immune from our own interpretive shortcomings and bad theology. We have less excuse than the Jews to hold such a de minimis view of neighborliness and love (because of the clear words of Jesus), but we can fall into the same interpretive trap.

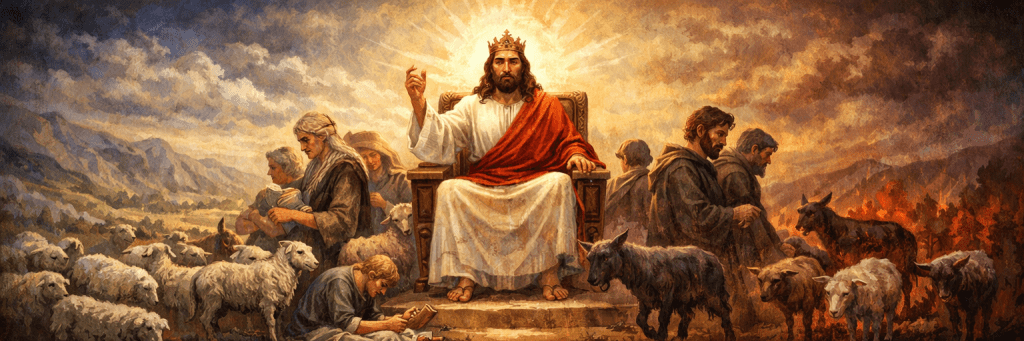

In that context, consider the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats.

Continue reading “How We Set Boundaries On Who Is Our Neighbor and the Least of These”