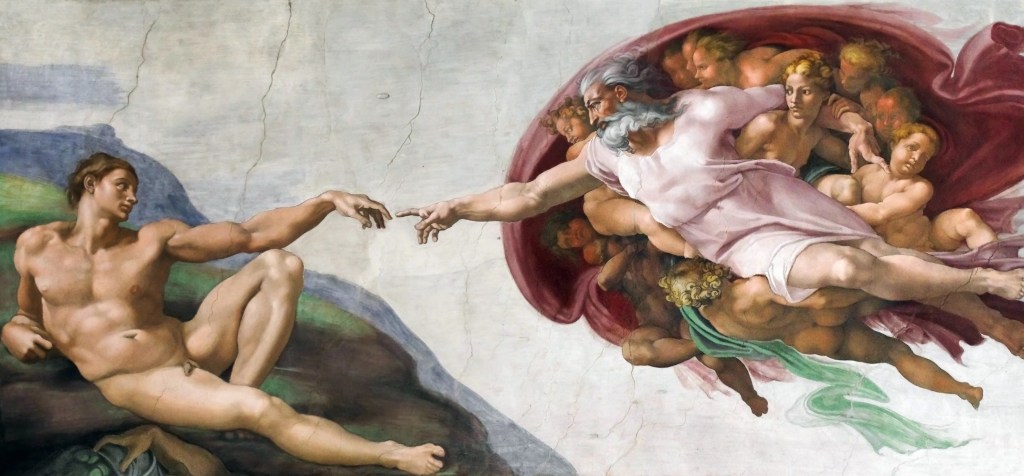

In a previous blog article, I tried to summarize the view developed by Old Testament scholar, Carmen Imes, on what it means that human beings are made in God’s image. I have only summarized her view as I understand it from a conversation on the Holy Post podcast (with some thoughts of my own added in), but she wrote a whole book about it!

The book, Being God’s Image: Why Creation Still Matters, was recently published as a prequel to her previous book, Bearing God’s Name: Why Sinai Still Matters. The previous book on bearing God’s name, in turn, was distilled from Imes’ doctoral dissertation.

Her observations are profound in my book! (Which I don’t have because I am speaking figuratively now.) Having summarized her view on human beings being made in God’s image, I am turning now to the significance of bearing God’s name and not taking His name in vain.

Imes says we don’t bear (take on) God’s image because we are (already made in) God’s image, but we do take on (bear) God’s name if we are His covenant people. The significance of taking on God’s name is what is implicated in the third commandment: thou shalt not take the Lord’s name in vain.

In Carmen Imes’ first book, Bearing God’s name: Why Sinai Still Matters, she explores the commandment not to take the Lord’s name in vain. She argues for what she calls “missional reading”. Thus, she says we should not understand this command simply as a rule to be applied to our speech and how we refer to God verbally. She says the meaning is much broader, deeper and more fundamental than that.

This commandment implicates our whole lives! We who take God’s name are His representatives in the world. We bear or carry His name, so what we do, and who we are, and how we represent God, who’s name we carry, matters deeply!

Every human being is made in image of God, but only God’s covenant people bear His name. Every member of the human race is invited to join the covenant community, but until people join themselves to God’s covenant community, they do not take His name.

Thus, Imes says, “It’s impossible for a nonbeliever to take God’s name in vain.” They haven’t taken His name at all, so they cannot violate the command not to take God’s name in vain. If a person doesn’t take God’s name in the first place, he/she cannot take His name in vain.

Remember that God revealed His proper name, Yahweh, only to His covenant people. Yahweh was not revealed to all people at the time the commandments were given to Moses. The name of God, Yahweh, was only revealed to Israel in the context of the covenant God made with them.

In New Testament verbiage, we are ambassadors of Christ if we have been born again and accepted Christ as our Lord. When we are born again, we take on the “heredity” of God as His children. When we accept Jesus as Lord, we “take his name”: we become identified as Christ followers, traditionally known as Christians.

Because we are followers of Christ who bear his name, everything we do and say is a reflection of Him. We are representatives of the kingdom of God. We carry His flag as we live our lives in the world. (If, indeed, we are not ashamed to be called by His name.)

Continue reading “What It Means to Bear God’s Name and the Significance of Not Taking God’s Name in Vain”