I am writing today about the Parable of the Good Samaritan and the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats in light of the Old Testament passage that introduces what Jesus called the second greatest commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. (Leviticus 19:18) If you have read anything I have written lately, you know that I have have been meditating on this theme.

How People Misinterpreted “Neighbor”

When Jesus encountered a First Century expert in the Law, the issue became: Who is my neighbor? The Parable of the Good Samaritan was the response from Jesus. The backstory to the Parable of the Good Samaritan reveals how First Century Jews misread Leviticus 19:18 to limit who they considered neighbors. It reads as follows:

“Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people, but love your neighbor as yourself. I am the Lord.“

Just 16 verses later (in Leviticus 19:34), Moses hints at a broader, more expansive meaning to the rule to “love your neighbor as yourself”:

“The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt. I am the LORD your God.”

Distinguishing Among Jews and Gentiles

In the time of Jesus, Jews distinguished between Abraham’s descendants and everyone else (Gentiles). They limited neighbors they were instructed to love to those from among their people because they interpreted Leviticus 19:34 in light of Leviticus 19:18. They interpreted “from among the people” to include descendants of Abraham, and they likely included those foreigners who lived among them and observed their religious practices, but they did not go further.

The Hebrew word translated “foreigner” in verse 34 is ger. It generally means “sojourner, stranger, foreigner, alien,” and it literally means “a guest.” (See Biblehub) Ger is derivative of guwr, which means “to sojourn, dwell, reside, live as a foreigner,” with connotations of being a guest, shrinking & fearing, and being afraid.

According to the topical Lexicon, gurw centers on “the act of taking up residence as a non-native, a ‘sojourning’ that is self-conscious of impermanence and dependence on the goodwill of the host community.” The sense of this word as scholars have come to understand it is of foreign guests who dwell permanently among the people and conform to the requitements of the Mosaic Law. I believe First Century Jews would have had a similar understanding of the concept of neighbor that defined who they were to love.

By the First Century, there were two categories of people: Jews and Gentiles. We know from historical records that some Gentiles lived harmoniously with Jews and more or less subscribed to Jewish religious customs as they were allowed to engage with them.

The Samaritans as Others

There were varying degrees to which Gentiles could be incorporated into Jewish community. Some Gentiles were circumcised, converted to Judaism, and were fully integrated into Jewish community. The largest group of Gentiles who lived among the Jewish community, however, were the “God-fearers”. They were welcome in the temple and synagogue. They participated in prayer and instruction. They ethically aligned with Jewish community, but they were not circumcised, not bound to the full Torah, and were not considered covenant members of the Jewish community.

These Gentiles who believed in God as the Jews did, who worshipped God as the Jews did, and who lived in harmony with biblical, ethical requirements were accepted in Jewish community. They more or less represented the ger in Leviticus 19. They, like the ger, were considered neighbors who must be loved.

The question posed by the expert in the Law in Luke 10 reveals that the scope of who is a neighbor was limited, but with some sense of uncertainty, in the First Century. That uncertainty was settled by Jesus in sharing the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

Samaritans and Jews Opposed Each Other

Samaritans were ethnically Hebrew. They descended from the northern tribes of Israel. They were descendants of Abraham, but they were deviant, ritually impure, and estranged from First Century Jews.

They were people who remained in the land after the exile to Babylon and integrated with the conquering Assyrians. They opposed the return of the exiles who rebuilt the Temple. They rejected Temple worship. They rejected the Levitical priesthood returning from Babylon, and they had their own religious practices.

The hostility between the Jews and the Samaritans was mutual. They were closely related by kinship, but they disagreed sharply over theology, religious practice, and heritage. They were estranged, avoided each other avoidance, and clashed (sometimes violently).

Insiders and Outsiders

Though the Jews would accept the Gentile converts and God-fearing Gentiles into Jewish community, Samaritans and other Gentiles were excluded. They were the people the legal expert’s question was about: Who is my neighbor? They were not from “among the people.”

Many people in the Jewish community, like the expert in the law, had a theology that excluded Samaritans and most Gentiles from the definition of “neighbor”. Their mistaken interpretation and bad theology created insiders and outsiders.

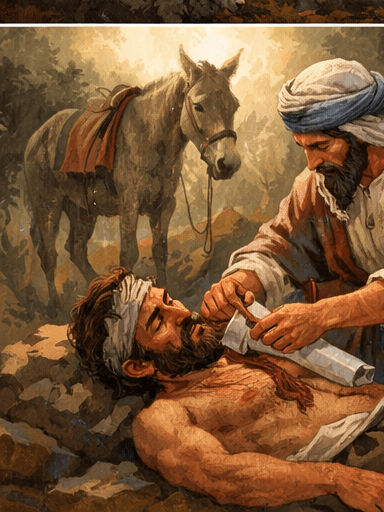

Jesus Cuts Against Our Insider Logic

Jesus reveals how God’s Word cuts against our insider logic. Jesus interprets Scripture and compels us to view our neighbors (whom we should love as ourselves) Expansively. Our neighbors include people who are not like us, people who are heretical and (therefore) threatening to us and people in opposition to us. Outsiders.

Jesus shockingly made a Samaritan the hero in the Parable. Most Jews would not have used “good” in the same sentence as a Samaritan. Samaritans were outsiders, people in opposition to the Jews, heretics, and estranged. Samaritans were not seen as neighbors, but Jesus disavowed them of their bad theology.

We know this, but we are not immune from our own interpretive shortcomings and bad theology. We have less excuse than the Jews to hold such a de minimis view of neighborliness and love (because of the clear words of Jesus), but we can fall into the same interpretive trap.

In that context, consider the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats.

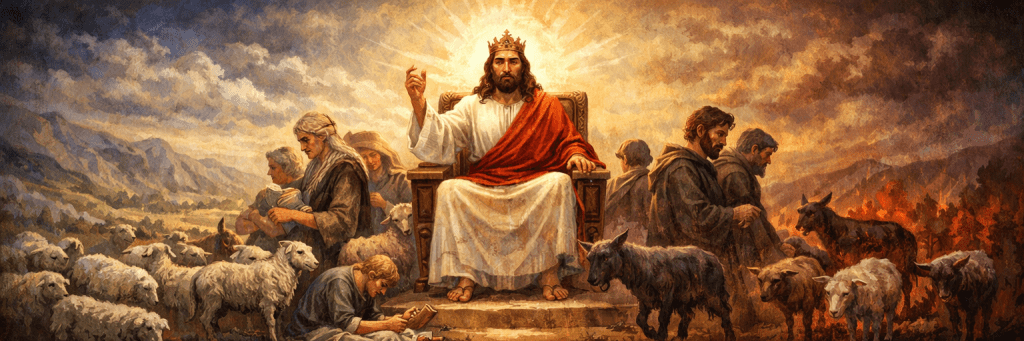

The Parable of the Sheep and the Goats

The Parable of the Sheep and the Goats is found in Matthew 25:31-46. This parable was shared by Jesus after he talked about the destruction of the Temple, signs of the end times, and how the day and the hour is unknown in Matthew 24. In Matthew 25, Jesus shares parables on how the kingdom of heaven will be like the Ten Virgins (some of whom were not prepared) and the Bags of Gold entrusted to servants (for which God expects some return). Then Jesus, shared the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats.

These parables describe how we should live in light of the destruction of the Temple, the end times, and not knowing when the end will come. When the end comes, “All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate the people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats.” (Matt. 25:32) The standard for separating people is deceptively simple: what they did during their lives for “the least of these my brothers and sisters of mine.” (Matt. 25:40, 45)

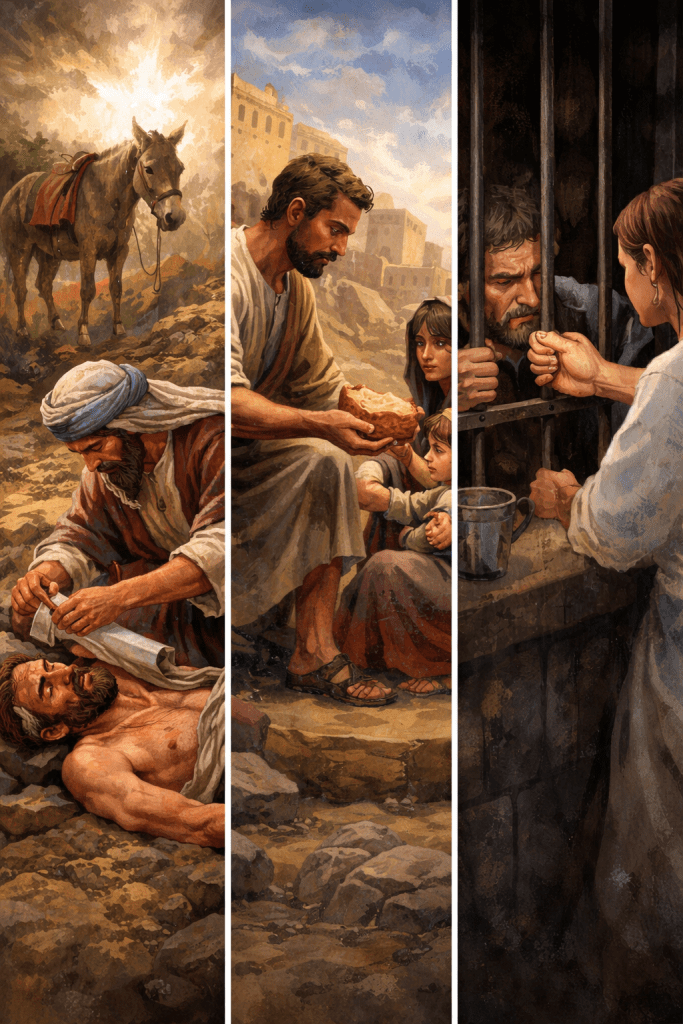

Those who fed the hungry, gave drink to the thirsty, invited the stranger in, clothed people, looked after the sick, and visited the prisoners were blessed and given their inheritance with the Father. Those who did not do these things were cursed and told to depart. The righteous are given eternal life, and the unrighteous were given eternal punishment.

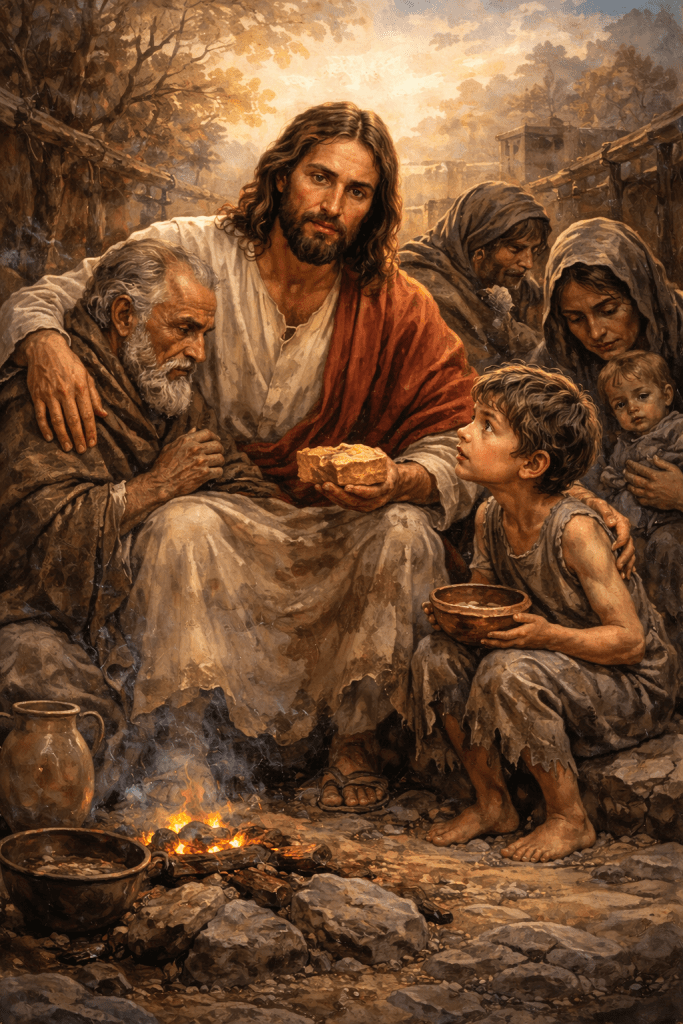

Jesus Identifies with the Least

A curious aspect of the Parable is that Jesus inserted himself into the parable and identified himself as the hungry, thirsty, naked, stranger, sick, and prisoner. Neither group understood that they were treating Jesus the way they treated the least – people in need.

We Make the Same Interpretive Mistake

To draw a parallel to the command to love our neighbors, some people have asked (like the expert in the Law): who are the the least these? For many people, the answer seems limited

“whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

Christians often read this passage with an interpretation strikingly similar to the way First Century Jews narrowed the meaning of neighbor in Leviticus 19. Many assume “the least of these my brothers and sisters” means only fellow Christians, members of one’s church, missionaries or persecuted believers, or the “deserving poor” within the faith community.

This reading feels plausible. After all, Scripture speaks of special obligations within the household of faith (Gal. 6:10). Yet, this limited interpretation mirrors the very limitation Jesus dismantled in the Parable of the Good Samaritan: defining love in ways that remain safely inside one’s own community.

The Importance of Context

We need to read Scripture in context. Context includes the surrounding passages, the history and culture of the time, other passages, and the arc and sweep of Scripture. Thus, we should be mindful of Leviticus 19 and the way First Century Jews missed its expansive meaning. We need to be mindful the way took them to task for that bad theology in the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

In Leviticus 19, if we consider our neighbor only to be those from among our own people, we are only half right. In parallel, then, we should consider that caring only for the least of these brothers and sisters of ours may only be half right.

Yes, of course, we should love our Christian brothers and sisters. That is the very least we should do as children of God, but we know that God does not stop there.

If God’s view was similarly limited, no Gentiles would be allowed “in” to relationship with Him. God’s design was more expansive than that from the beginning. He purposed to bless “all the nations” through Abraham – not just Abraham’s descendants.

The Context of All the Nations

The Parable of the Sheep and the Goats is constructed in the context of the gathering “all the nations” at the end of time. The list of those with whom Jesus identifies includes the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the naked, the sick, and the imprisoned. The inclusion of the stranger is telling. It evokes the vulnerable outsider and puts the foreigner in the center of the final judgment scene.

In the Parable of the Good Samaritan, the hero is not a member of the covenant community of God. The Samaritan is unexpectedly considered the insider.

In the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats, Jesus unexpectedly identifies with people in need – vulnerable people on the margins. He calls them “brothers and sisters of mine.” By doing that, He brings the outsiders in and challenges us to embrace them as neighbors whom we should love.

The Shock of Recognition

Both parables share a destabilizing feature:

| Parable | Expected Insider | Unexpected Model of Righteousness |

|---|---|---|

| Good Samaritan | Priest & Levite | Samaritan outsider |

| Sheep & Goats | Religious adherents | Those who served the vulnerable (knowingly or not) |

God Identifies with the Vulnerable

Indeed, we see throughout Scripture indications that God generally identifies with and has peculiar affection for vulnerable people. These passages are stated without any qualification:

Psalm 68:5 —

“A father to the fatherless, a defender of widows, is God in his holy dwelling.”

Deuteronomy 10:18 —

“He defends the cause of the fatherless and the widow, and loves the foreigner residing among you, giving them food and clothing.”

Proverbs 14:31 —

“Whoever oppresses the poor shows contempt for their Maker, but whoever is kind to the needy honors God.”

Proverbs 19:17 —

“Whoever is kind to the poor lends to the Lord, and he will reward them.”

God’s Commands without Qualification

God’s commands to His people to love and care for vulnerable people are also without qualification:

Exodus 22:21–24 —

“Do not mistreat or oppress a foreigner… Do not take advantage of the widow or the fatherless.”

Isaiah 1:17 —

“Learn to do right; seek justice. Defend the oppressed. Take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow.”

Zechariah 7:9–10 —

“Administer true justice; show mercy and compassion… Do not oppress the widow or the fatherless, the foreigner or the poor.”

Jeremiah 22:3 —

“Do no wrong or violence to the foreigner, the fatherless or the widow.”

The Stranger in the Middle

The stranger is especially telling in all of this. A stranger (xenos in the Greek — foreigner, outsider) is, by definition, an outsider. A stranger is not one of us.

The inclusion of the stranger in these lessons shares continuity with Leviticus 19. It invokes the memory of Israel’s shared experience – “Because you were foreigners in Egypt.” (Lev. 19:34) Jesus extends that memory to himself in saying, “I was a stranger and you invited me in.” (Matt. 25:35)

The stranger in the middle challenges us to let go of our insider logic and to see people as God sees people – lost sheep in need. God sent His only Son into the world for them, and Jesus commissions us to go out into the world for them also.

Where We Repeat the First Century Error

We are tempted to ask the same limiting question in new forms. “Who is my neighbor?” turns into “Who are the least? Who is truly deserving of aid? Should we prioritize our own? What about those whose beliefs or lifestyles differ from ours? What about those who oppose us?

These questions often function less as moral discernment and more as boundary markers — ways to keep love manageable. Ways to insulate ourselves from the transformative change of heart needed to love people we do not like.

Like the legal expert in Luke 10, we seek clarity that will allow us to fulfill the law without being truly transformed by it. If we do not accept the challenge from Jesus, we will be not transformed by him. We will end up on the wrong side of the separation of the sheep and the goats.

The Danger of Theological Minimalism

The First Century narrowing of “neighbor” allowed love to remain tribal. A similarly narrow reading of Matthew 25 allows compassion to remain similarly tribal, ecclesial rather than incarnational. Though the image of God is stamped on all human beings, we only honor it in the people we are comfortable including in our circle.

The teaching of Jesus challenges our desire to limit love. If the Samaritan is neighbor, and if Christ is present even in the stranger, then love cannot be confined to shared doctrine, shared ethnicity, shared citizenship, shared morality.

The kingdom ethic is not love your own as yourself but love others as yourself . Period, Full stop. Love is not bounded. Love extends to all people because all people are stamped with the image of God.

The Eternal Weight of Ordinary Mercy

One of the most remarkable aspects of Matthew 25 is the fact that ordinary acts carry such extraordinary weight: giving food, offering water, practicing hospitality, welcoming strangers, caring for the sick, visiting the imprisoned.

No miracles. No theological treatises. No public displays of piety. The way we conduct ourselves every day in every little way – the things we do and the things we do not do – have eternal weight. Literally, anyone and everyone can do these things.

The final judgment turns on whether love crossed boundaries. We cannot stop at those who are like us and those whom we like. God did not stop with Abraham and his descendants. God intended from the beginning to extend His blessing to all the nations. Jesus told us to go into all the world – to cross all boundaries.

From Egypt to the End of the Age

A straight line runs through Scripture:

- Adam & Eve as exiles → begins the story of God’s redemption

- Israel as foreigners in Egypt → empathy grounded in memory

- Leviticus 19 → love extended to the ger (the foreigner)

- Sermon on the Mount→ neighbor includes the enemy

- Good Samaritan → neighbor includes the estranged

- Sheep and Goats → Christ encountered in the vulnerable outsider

This is not a new ethic. It runs underneath all of Scripture like a stream of living water. We were all exiles in God’s fallen world – estranged from Him. God sent His only Son to us. Jesus tore down the dividing wall. He stands at our door and knocks. He sends us out to the whole world – without limitation – to share the good news that God desires to welcome us in.

A Question that Still Judges Us

The legal expert asked, “Who is my neighbor?” In the same way we, wonder, “Who are the least of these?” The question begs for definition, limits, and boundaries to our love. The answer Jesus gives us to set that question aside – love has no boundaries. It extends even to those who oppose us and even to our enemies who persecute us.

ALL people are made in the image of God. God purposed to bless All the nations. For God loved ALL the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish but have eternal life. Jesus commissioned us to go into ALL the world making disciples.

God does not limit His reach. We should not limit our response. Even in a verse cited by those who would limit “the least of these brothers and sisters of mine” to followers of Jesus, there are no limits:

“[L]et us do good to all people, especially to those who belong to the family of believers.“

Galatians 6:10

Our love naturally – especially – begins within the Body of Christ, but it does not end there. God’s love compels us to go out and bring others in. No one is an outsider to God’s love, and no one should be excluded from our love. Everyone is our neighbor, and everyone who has need is worthy of our care and attention.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer: All of the ideas and themes in this blog are mine, but I have used AI to organize them and to generate graphics.

This was a beautiful read ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

❤️ I can’t wait to read what you have coming up next Kevin! Have a wonderful Taco Tuesday!

LikeLiked by 1 person