What does it mean that human beings are made in God’s image? What does it mean that God commands us not to take His name in vain? New answers to these interrelated themes might surprise you.

Carmen Imes wrote a book called Bearing God’s Name that explains for common folk like me the conclusions she developed in her doctoral dissertation. She just published a new book called Being God’s Image, a kind of prequel to the first book. I recently listened to her talk about these things with Skye Jathani on the Holy Post podcast that inspires my writing today. (The conversation starts at 54:20 if you want to hear it from her mouth.)

The commandment not to take God’s name in vain is where the conversation started, but being made in God’s image is actually the prequel to that “story”, and the significance of bearing God’s name (in contrast to being God’s image) is central to the story.

I am going to start with the backstory (in the beginning), what it means to be made in God’s image, and what it means to bear God’s name before opening a new understanding of the commandment not to take God’s name in vain, according to Carmen Imes.

Imes says that some theories entertained by the church misperceive the significance of the revelation in Genesis to people in that culture filled with false idols. They miss the mark and fall short of the reality that is expressed in Genesis.

Imes says, “The majority of the views out there through the centuries attached the image of God to some human capacity or function. That view makes the image of God something we do or are qualified to do by having a certain capacity.”

Some say human rationality is what it means to be made in the image of God. They reason that we are intellectually superior to animals; therefore, rationality is what it means to be made in the image of God.

Others have ascribed being made in the image of God to our social and political ability to govern ourselves. Still others believe our morality and conscience are what distinguish us from the animals as being made in God’s image.

These things certainly distinguish human beings from other creatures created by God, but Imes says these human capacities, true as they are, do not accurately convey what the biblical text actually says. Imes says that assuming the differences between humans and the animals is what being made in the image of God means s just “theological speculation” It is eisegesis – imposing our own thinking on the text – rather than exegesis – extracting the meaning from the text, itself.

Th view that special human capabilities are what it means to be made in the image of God is not true to the biblical text, and it is not justified by the text. Exegesis of the text (pulling the meaning from the text, and not from our conceptions applied to the text) reveals a different view for what it means to be made in God’s image.

Imes says we need to pay closer attention to what the text actually says to determine its meaning. She also reads the text in light of its context, the Ancient Near Eastern culture, to determine more precisely what it means that human beings are made in the image of God.

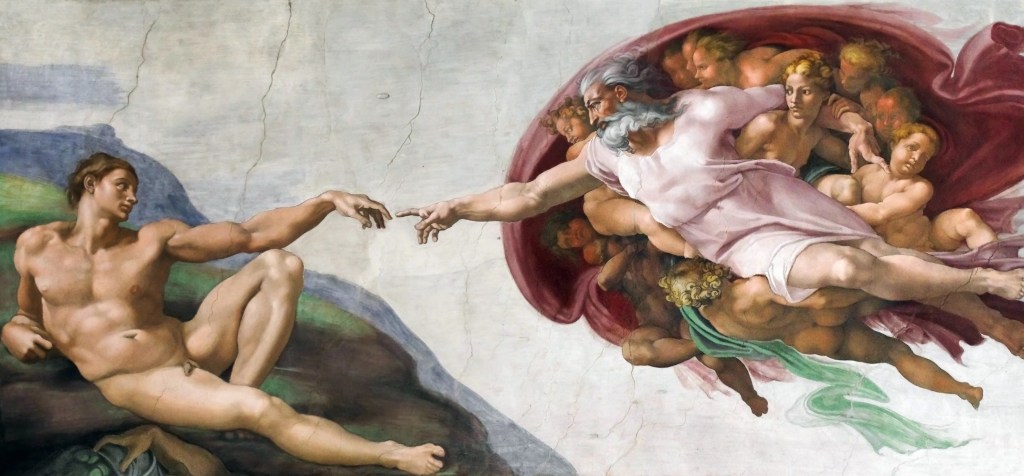

The backstory begins in Genesis 1:27:

God created mankind in his own image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

The Hebrew word translated “image” in this passage is tselem, meaning literally an image. Strong’s Concordance describes the word further as “a phantom, i.e. (figuratively) illusion, resemblance; hence, a representative figure, especially an idol — image, vain shew”. (See BibleHub)

We resemble or are representative of God, though we are not (yet) true representations of God. Given the Hebrew meaning of the word, tselem (with overtones of “phantomlikeness” and resemblance – implying something less than the real thing), perhaps we are merely phantom resemblances at this time.

I would note that we may only have the potentiality of being truly like God. In the New Testament, we find that we must be born again to become God’s progeny, His children, his ambassadors (representatives) and to be found “in” Christ, who alone (at this time) is the exact representation of God in the flesh (not merely a resemblance).

Perhaps, we only have the potentiality to be exactly like God, but that doesn’t discount the fact that we are created in His image – as Adam and Eve were created in His image. This understanding sheds new light, perhaps, on the first commandment: “Thou shalt have no other gods before me”; and it sheds new light on the second commandment: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.”

I am going beyond, now, what Carmen Imes says in the conversation, though I think it follows from her observations. I will also get to the surprising nuance she finds in reading Genesis 1:26-27* that sets this text apart in the Ancient Near Eastern culture.

Ancient Near Eastern people, like most people of that age, confused God with His creation and worshipped various aspects of the creation, such as trees and mountains, the sun and the moon, etc. They also conceived gods with personalities that animated these things, and they made idols in the images of those gods to venerate and worship.

When God forbids his covenant people from having any other gods before Him, He is conveying to them something of the nature of Himself and the world – that God is “other” than His creation. The commandment is a instructive about who God is.

When God forbids His covenant people to make any graven images, He is not just telling them something about Himself. God is conveying something about what it means to be human – that we, alone, are representative of (images of) God in His creation. In that sense, humans are the only authentic “idols” of God

Carmen Imes observes that being made in God’s image is characteristic of every human being. Every human being is made in the image of God. All of us (male and female) are images of God.

In that light, the commandment to love God and love your neighbor takes on new significance. We love God because He alone is God, and we love our neighbor because He made us (including our neighbors) images (idols) of Himself. That means that all human beings have intrinsic value.

God made images (idols) of Himself, and we are them! In that sense, we are God’s “true idols”. All the idols made by men are false idols.

The Hebrew word translated image tselem (and resemblance or representative) is used many places in Scripture to mean an idol. (For example, Num. 33:52; 1 Sam. 6:5; 2 Kings 11:18; and 2 Chron. 23:17) It’s exactly the same word.

Tselem was used this way not only in the Bible, but throughout the ancient world. Related languages, like Akkadian and Ugaritic use the same word to mean the same thing. Thus, tselem is the same word used ubiquitously in the Ancient Near East to refer to the idols (images/representatives) that people made of the gods of that time period.

When Genesis says that God made human beings in His image, it would have been understood in light of all the images (idols) found in the various cultures of the Ancient Near East. In the context of Genesis Chapter 1, as a whole, we understand that God (Yahweh) created everything, and He stands apart from all that He made. Of all the creatures God made, God made only human beings “in His image.”

While most people talk about “bearing God’s image,” Imes says she no longer views being made in the image of God in those terms. A person who bears God’s image can “set it down”, but the image of God is not something we put on or take off. It is something more fundamental than that. It is embedded in who humans are.

The image of God isn’t something we can adopt or abandon. It isn’t something we can take up and put down. It isn’t a function, or a capacity, or a capability; it is something we are by virtue of God making us that way. We are made in God’s image. Thus, every human being is the image of God.

This leads Imes to conclude that we need to view ourselves as three-dimensional representatives of God. We are “God’s idols”. We are the only true idols, because we are made by God to be representative of Him. All other idols (tselem) are false idols.

False idols are inanimate representations of the concepts of the gods. We are animate representations of God, the only true and living God!

Thus, the image of God isn’t attached to a specific capacity that human beings have. The image of God is our human identity.

We can’t lose it. We can’t set it down. We can’t put it on, and we can’t take it off. “It’s intrinsic to being human. Every human being who has a body is the image of God.”

For these reasons, Imes titled her new book, Being God’s Image (not bearing God’s image). God made us the embodied images of Himself, and nothing we can do changes who we are. We are God’s image.

Since being made in the image of God is nothing that we do, all humans, regardless of capacity, or functionality, or capability are equally made in the image of God. All humans are representative of God.

Paul echoes this idea when he says there is no Greek nor Jew, slave nor free, male nor female in Christ. People in Christ are all equals, having equal worth that is intrinsic in what it means to be in Christ.

According to Imes, this is enough to warrant treating all humans according to the value intrinsic in us, created in us by God, Himself. There is no black nor white, no genius nor imbecile, no abled nor disabled in God. We are all equally made in God’s image. For this reason, we value human life in the womb. We value all human life that exists without qualification.

Perhaps, we only truly characterize and encapsulate what it means to be made in God’s image in Christ. Before that, we have all the potentiality of being made in the image of God. In Christ, that potentiality begins to become reality!

The ultimate significance of human beings being made in God’s image is that we love (value) our neighbors and even our enemies. To do anything less is to denigrate and demean God’s very image.

If all it means for us to be made in the image of God is that we are different than the animals in our capacity, functionality, and capability, then we might begin to think that some humans are more (or less) images of God. We might value some humans more and some humans less for their relative differences in capacity, functionality, and capability.

We don’t see humans treated in this way by Jesus, however. He told the adults that they would not enter the kingdom of God unless they became like children. He said the first will be last, and the last will be first. He said the person with one talent who uses what they have to glorify God is no different than the person who has many talents.

If God’s image is not something humans beings bear, but rather something they are, the idea of bearing God’s name as His covenant people and not taking His name in vain gains new significance, says Carmen Imes. I will tackle the idea of bearing God’s name and not taking His name in vain in a future blog article.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

* 26 Then God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.”

27 So God created mankind in his own image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

One thought on “The Surprising Significance of Being Made in God’s Image”