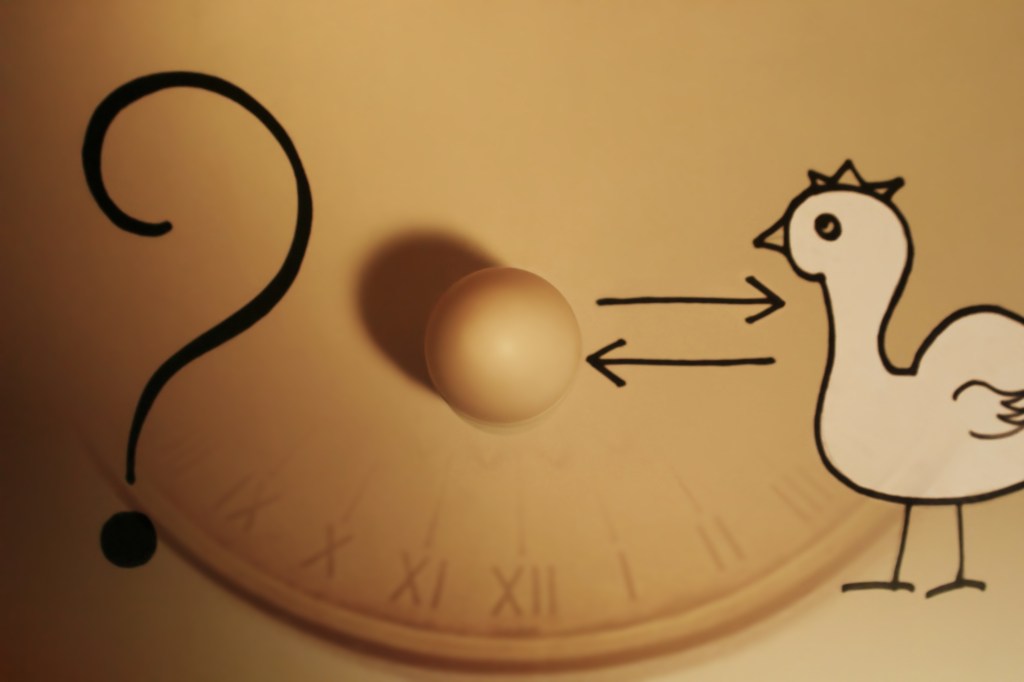

Which came first? The chicken or the egg? This is a school child’s question, but sometimes the most profound questions about life and reality as we know it can be boiled down (to keep with the theme) to simple questions and simple propositions.

Spoiler alert: I am not going to take a position on the chicken/egg controversy. That was just a teaser. The questions I want to address are far more fundamental (though actually related).

The assumptions we make, even the greatest geniuses among us, are pretty simple at their core. And we can’t prove them. We have to take them on “faith”, yet we construct our view of the world and how it works on the basis of those assumptions.

Many people develop those assumptions from an early age without much critical examination. Though our basic assumptions are the filter through which we view everything, and we use those filters constantly to make critical examinations of the world around us, we rarely examine or critique those filters, themselves.

Because our assumptions are the basis on which we reason, do science, and live our lives, we tend to be reluctant to subject them to rigorous examination. Two of the most fundamental filters by which people see the world are diametrically opposed to each other: 1) the assumption that a divine being exists through which the universe was created, and 2) the assumption to no such divine being exists, and all that exists is physical matter and energy.

(A third view is that the divine “entity” is one with matter and energy, but this view can be lumped in with the view that all that exists is matter and energy since this third view equates the divine with matter and energy. Only the first view assumes that divine reality exists separate and apart from matter and and energy and caused it to come into being.

I note that many people try to mix and match these fundamental assumptions. The view that the divine is “one with” and undifferentiated from the matter and energy that makes up the universe is such an attempt, and it runs into problems as a result.)

The assumptions could not be more simply stated: either God exists, or God does not exist. We vigorously defend whichever of these two assumptions we have embraced. We cannot definitely prove either of these assumptions, but we are often loathe to subject them to critical examination.

That doesn’t mean that we don’t “test” them. In some ways, our daily lives are a continual test of those basic assumptions – consciously or unconsciously. As we live our lives, our assumptions are repeatedly put to the test as we apply the filters derived from our assumptions.

I think all people have encountered some disconnection between reality and their basic assumptions. I think we have all struggled with feeling like the world doesn’t make perfect sense – it doesn’t add up according to our assumptions. I submit that is the inevitable state of a finite being who doesn’t know what she she doesn’t know (and, perhaps, never will).

Human beings are nothing, however, if not resilient. We are good at ploughing forward with vague feelings of unease that our basic assumptions are not adding up. We may not always be conscious of this unease. Some people simply shrug their shoulders and resign themselves to it.

“Eat, drink, and be merry” (for tomorrow we die), is the attitude people often hold onto who have reached a state of mental and emotional confusion and resolved it with indifference. Life has a way of confronting that indifference, however, when loved ones die, injustice hits close to home, and the age old question, “Why?!” pushes to the surface like rocks in a New England yard after a hard rain.

I submit that our faith is revealed in the way in which we hold to those assumptions, believing that they will be vindicated, despite the incongruities between those assumptions and the reality that continually confronts us. We put our trust in those assumptions and plow forward, moving the rocks to the edges of our intellectual territory.

Frankly, what else is a finite being to do?

A friend of mine, when I posed the question about the chicken or the egg, said the answer is easy: the egg came first. I don’t know whether he was being facetious or serious, but his confidence illustrates the point that we have faith/trust in our basic assumptions. He can’t prove the egg came first, but he was confident in his assumption.

In the following presentation, Sy Garte unpacks the basic chicken and egg question about the origin of life. Sy Garte is a scientist, a biochemist, who is retired from a career in science. He is published in scientific journals, and he is very familiar with the challenge of unpacking those basic assumptions.

His father was also a scientist. He grew up in an atheistic household that was hostile to the idea of God. He assumed that no God exists, and the world consists only of matter and energy into his 40’s.

At that point, he changed his mind on his basic assumptions. It was science that led him to question his basic assumptions and, eventually, to examine them rigorously. He came away from that rigorous examination with a new set of basic assumptions that, he says, make much more sense of science and reality.

If you are interested in his story, he wrote a book about his journey from a purely materialistic view of the world to the view that God exists: The Works of His Hands: A Scientist’s Journey from Atheism to Faith. But that isn’t the subject of my writing today.

I write today on the subject of our basic assumptions, and how they affect the way in which we approach the world. I hope you will take the time to watch the following presentation, which demonstrates how those basic assumptions affect our thinking. The presentation is only about 27 minutes long with Q & A at the end.

He presents the chicken and the egg question in two syllogisms. The first one is the assumption he grew up with and which formed the basis of his views for over 40 years:

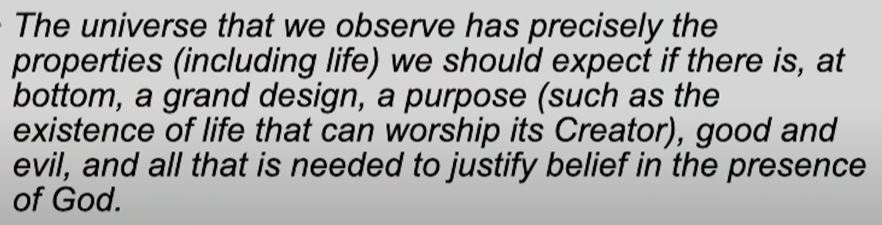

As noted above, he was led to reexamine his basic assumptions through science. First, it was physics that posed a challenge to his basic assumption that no God exists. Much later, his beloved biochemistry led him further down the path. The second syllogism is the one he know assumes:

I have often thought of the importance of perspective for finite beings such as humans. Our individual and collective perspectives are unique and fixed in time and space to a very small connection with the universe. We are parochial with our perspective, and we tend to be adverse to other perspectives breaking in on our little corners of the universe. But, the universe is vast, and we should not be so fearful or defensive as to shield ourselves from other perspectives.