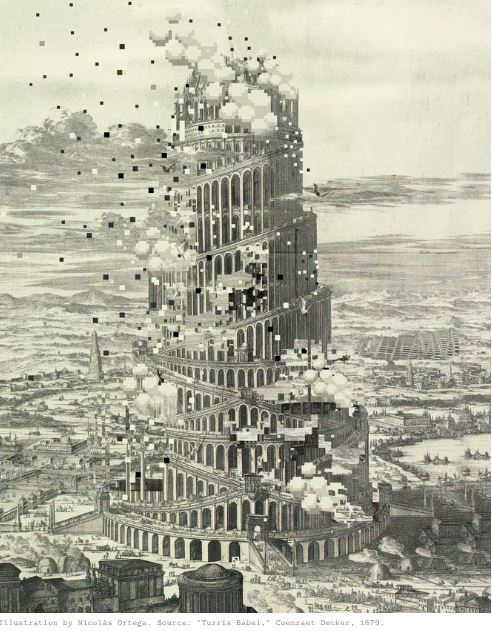

Jonathan Haidt wrote this week in the Atlantic, “The story of Babel is the best metaphor I have found for what happened to America in the 2010s, and for the fractured country we now inhabit.” He says,

“Something went terribly wrong, very suddenly. We are disoriented, unable to speak the same language or recognize the same truth. We are cut off from one another and from the past.”

I resonate deeply with this.

Haidt observes that we are “becoming like two different countries claiming the same territory, with two different versions of the Constitution, economics, and American history.” Many people talk about the tribalism of our times, but Haidt suggests that tribalism isn’t the most accurate description of what is going on. Haidt finds the clearest understanding of the polarization of our times in the story of the Tower of Babel:

“Babel is not a story about tribalism; it’s a story about the fragmentation of everything. It’s about the shattering of all that had seemed solid, the scattering of people who had been a community. It’s a metaphor for what is happening not only between red and blue, but within the left and within the right, as well as within universities, companies, professional associations, museums, and even families.”

Haidt focuses blame on social media. He identifies 2011 as “the year humanity rebuilt the Tower of Babel” with Google Translate symbolically bridging the confusion of different languages. He says (for “techno-democratic optimists”), “[I]t seemed only the beginning of what humanity could do.”

Around the same time, Zuckerberg proclaimed “the power to share” a catalyst to transform “our core institutions and industries”. He may have been prophetic, but I doubt he envisioned such a corrosive change.

Haidt, something of a social scientist, himself, says, “Social scientists have identified at least three major forces that collectively bind together successful democracies: social capital (extensive social networks with high levels of trust), strong institutions, and shared stories.” Social media substantially weakens all three of these fundamental building blocks of a cohesive society.

It started harmlessly with the sharing of personal information to stay connected, but it quickly morphed into a kind of personal performance and branding platform. Along the way it developed into powerful weaponry at the fingertips of anyone and everyone at once.

The “Like” and “Share” buttons became commodities of individual enterprise and personal combat. Algorithms exposed (and exploited) the emotional currency of heightened individuality and the power of anger.

“Going viral” fed the hopes of Internet junkies like the possibility of a jackpot snares gambling addicts in its steely fingers, and the stakes were just as high. Haidt says, “The newly tweaked platforms were almost perfectly designed to bring out our most moralistic and least reflective selves. The volume of outrage was shocking….” The rapidity and its ability to spread was more virulent than COVID, or the plague.

Haidt lauds the framers of the Constitution for designing a republic built on “mechanisms to slow things down, cool passions, require compromise, and give leaders some insulation from the mania of the moment….” Haidt recalls Madison’s warning of “the innate human proclivity toward ‘faction’” so “inflamed with ‘mutual animosity’” that people are “more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to cooperate for their common good.’”

Haidt recalls also that Madison warned of a human tendency toward “factionalism” that can fan “the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions” into passions that ignite our most violent conflicts. Social media has ultimately proven him right.

Thus, Haidt says, “Social media has both magnified and weaponized the frivolous,” chipping away at our trust. The loss of trust makes every decision and election “a life-and-death struggle to save the country from the other side”.

The sagging number of people who have faith in their elected officials hangs at an all time low. In my lifetime, the United Sates of America has gone from a high of 77% trust in the federal government (1964) to a low of 17% in 2019. (See Public Trust in Government: 1958-2021, by PEW Research May 21, 2021)

Social media has corroded trust in government, news media, institutions and people in general. Some claim that social media may be detrimental, maybe even toxic, to democracy, which requires “widely internalized acceptance of the legitimacy of rules, norms, and institutions” for survival. “When people lose trust in institutions”, says Haidt, “They lose trust in the stories told by those institutions.”

Insiders have been warning us of “the power of social media as a universal solvent, breaking down bonds and weakening institutions everywhere”, while offering nothing in return but the chaos of utter freedom and will. Haidt references movements like Occupy Wall Street, fomented primarily online, that “demanded the destruction of existing institutions without offering an alternative vision of the future or an organization that could bring it about”.

We have become a society of “people yelling at each other and living in bubbles of one sort or another”, says former CIA analyst Martin Gurri, in his 2014 book, The Revolt of the Public. The people behind the social media giants may not have intended such a result, but they have “unwittingly dissolved the mortar of trust, belief in institutions, and shared stories that had held a large and diverse secular democracy together”.

Haidt claims he can pinpoint the proverbial fall of the American Tower of Babel to the intersection of “the ‘great awokening’ on the left and the ascendancy of Donald Trump on the right”. Haidt doesn’t blame Trump for the fall; he merely exploited it. Trump proved that outrage is the currency of the post-Babel economy in which “stage performance crushes competence” and Twitter overwhelms newspapers and the nightly news, fracturing and fragmenting the truth before it can spread and take hold.

“After Babel”, Haidt says, “Nothing really means anything anymore––at least not in a way that is durable and on which people widely agree.” Haidt is particularly morose on the prospect of overcoming the rapid dissolution of the American democracy. Unfortunately, I share his pessimism. How did we get here? How do we move forward?

Continue reading “Jonathan Haidt and the Erosion of American Democracy by the Corrosive Waters of Social Media”