My thoughts today might seem a little obscure, but let me set the stage first. Imagine the scene when two followers of John the Baptist were sent to ask Jesus a question. News of what Jesus was doing had traveled far and wide. People even reported that Jesus brought a dead man to life!

This is the backstory. Jesus happened upon a funeral procession. (Luke 7:11-17) The dead man being carried to his final destination was the only child his mother had, and she was a widow. Jesus was filled with compassion, ands he did the unbelievable. Jesus brought that dead man back from death!

This man and his mother were locals. They lived in a nearby town. They were talking, and it wasn’t just them. People saw it, and they were talking about it also. A crowd had witnessed the whole spectacle.

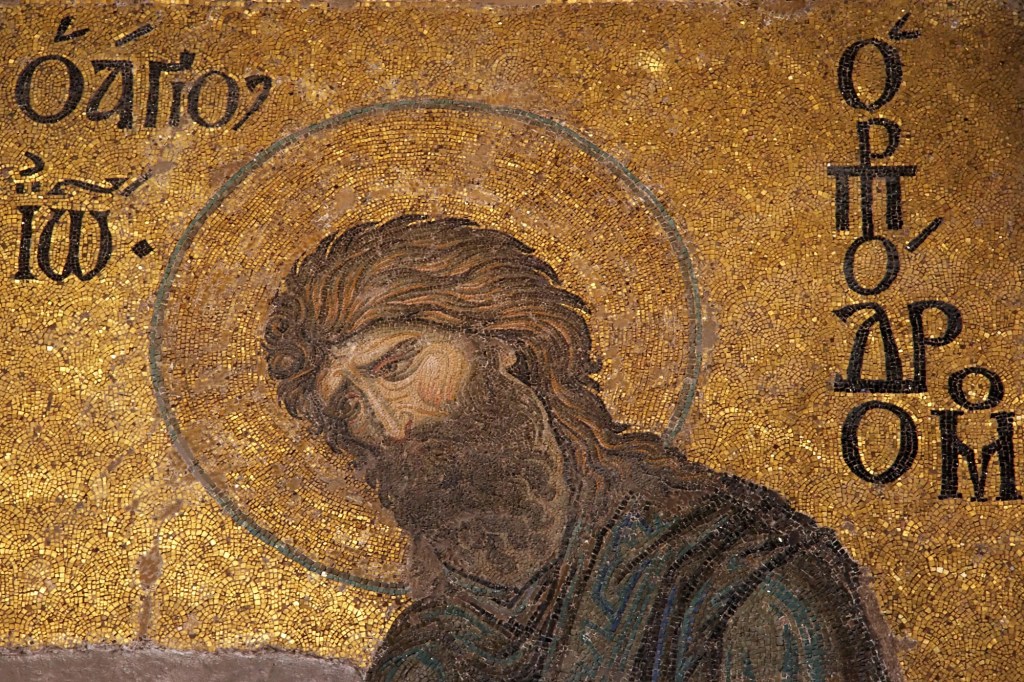

News about Jesus spread throughout Judea and the surrounding country, so that people were coming to Jesus from all around. John the Baptist heard about these things also, and he sent two of his followers to ask, “Are you the one who is to come, or should we expect someone else?”

(Luke 7:20) (As an aside, Luke does not tell us why John did not come himself, but we know from Mathew that John was in prison. (Matthew 14:1-12)

The “one” John the Baptist wondered about is the Messiah who had long been expected. John and his ancestors kin had been reading about the Messiah in the prophets for centuries. The time seemed right. Many had come recently, claiming to be him, but they were killed, and their following faded. Still, expectation was in the air.

John was imprisoned because he was open and blunt with criticism of Herod the Tetrarch, the local governor, who married his brother’s wife. Herod imprisoned John to silence him.

John was equally straightforward and to the point with the question he sent his followers to ask, “Are you the one?”

John the Baptist’s followers arrived on the scene as Jesus was curing people with diseases, sicknesses and evil spirits, healing people and even giving sight to the blind. When they asked him whether he is the one, or whether there is someone yet to come, Jesus said

“Go back and report to John what you have seen and heard: The blind receive sight, the lame walk, those who have leprosy are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the good news is proclaimed to the poor. Blessed is anyone who does not stumble on account of me.”

Luke 7:22-23

These words were familiar to John. They come from the book of Isaiah, one of those the prophets that foretold the Messiah to come (see Isaiah 35:5 and 61:1). The Messiah was predicted to be the cornerstone of a new order, but the prophets also warned that he would be rejected, and he would be a stumbling block for many. (See here)

The Pharisees and religious leaders also would have known exactly what Jesus alluded to in his response to John’s followers, though they didn’t even ask the question, and they probably were not privy to the answer. For them, Jesus was a stumbling block. The way Luke describes their response is what prompts me to write today.

We are not told whether the Pharisees and religious leaders were present when Jesus answered the question posed by John’s followers, but they might have heard about it. They followed closely what was going on with Jesus.

If Jesus did such miraculous things, then, why didn’t they believe? That seems like a fair question. Especially in that time. People were not predisposed, then, to disbelieve in miracles like people are today.

The Pharisees and Sadducees had other predispositions. (We all do.) Jesus was a threat to them because he did not come up through their ranks. He was not one of them. He seemed to stand separately and apart from them.

Jesus also didn’t seem to align with them in their theology and practices. (Not that the Pharisees and Sadducees were aligned with each other. They were not.) We may not know all the ways in which Jesus seemed to challenge the understanding of the religious leaders at the time, but one theme stands out: healing on the Sabbath.

We know from many other accounts that the Pharisees, in particular, criticized Jesus for healing on the Sabbath. As the religious authorities, they laid down the law on Sabbath observances, and Jesus did not confirm.

Maybe it was pride. Jesus was young. They may have felt that he had not earned the right to stand among them and pontificate.

Maybe they were jealous. Jesus seemed to be showing them up. People seemed to flock to Jesus. Maybe they were even threatened by the influence Jesus seemed to have on their people.

The particular account in Luke’s Gospel referenced above gives us only the following insight:

”[T]he Pharisees and the experts in religious law rejected God’s purpose for themselves, because they had not been baptized by John.”

Luke 7:30 NET

The way Luke describes their response to Jesus is curious to me. I might expect Luke to say they did not get baptized because they didn’t believe. If they didn’t believe John, who was sent to prepare the way for Jesus, they would not believe Jesus.

Instead, Luke says, “They rejected God’s purpose for themselves, because they had not been baptized….”. In essence, it seems that Luke is saying they didn’t believe because they had not been baptized.

I have come to notice, with the help of others, that we should always stop and dig a little deeper anytime we find something curious in scripture. I am not sure that I see or understand all there is to see or understand in this passage, but this curious phrasing prompts some thoughts today.

People tend to believe that we reason to our convictions, and then e conform our actions to our convictions. Some knowledgeable people who study these sorts of things question the order of our reasoning, beliefs, and actions.

We may think that we reason to our beliefs, and then we act. What if our actions are a tail that sometimes wags the dog? What if we are shaped more by our visceral reactions and reflexive actions than we care to admit?

Jonathan Haidt argues that we form our basic assumptions that drive how we view the world at a gut level. He says we don’t develop our worldviews at the level of the conscious mind. He claims with some good evidence that we only employ reason to defend the assumptions we make at a gut, emotional level.

Scripture seems to assume in its insistence on holding people accountable for their own sin that people have some agency in the way they conduct themselves. So Why did Luke put it backward, saying the Pharisees didn’t believe because they were not baptized?

We should know that reality is much more nuanced than it appears on the surface. We can’t always trust what appears to be true. We know in our minds that magic performed by a magician isn’t really magic.

Richard Dawkins agrees with theists that life seems to be designed, but he insists it really isn’t. Darwin admitted to a conviction that life seems to have purpose, but he didn’t trust his convictions. He reasoned to the conclusion that life isn’t purposeful with the help of his theory of evolution based on random, beneficial mutations.

Both of them admitted to gut level assumptions, but they reasoned to different conclusions. In Dawkins’ case, he was turned off by religion in his early years and became repulsed by it. Darwin lost a child, and that loss haunted him. According to Haidt, these gut level reactions likely drove their logic.

Dawkins was very young when he stopped believing in God. Dawkins’s science suggests that young men’s minds are not fully mature until about age 25, but Dawkins formed the lifelong beliefs that he has dogmatically defended all his life at about half that age.

The visceral assumptions we make that underlie our deepest convictions often develop subconsciously. We may not even know or be aware of their origins, yet they drive our most basic thoughts about the world and the way it works.

This suggests that our reactions to things and the actions that naturally follow from them may have more to do with our beliefs than we know. We defend our beliefs at a conscious level, but we may tend to form our beliefs at a more subconscious level.

The extent to which our visceral reactions drive our actions that we, then, defend by our reasoning, we entrench our beliefs with our rational abilities that are initially formed at a non-rational level. Visceral reactions, unchecked (and largely unnoticed), form habits in our actions and ways of thinking that we repeat over and over to ourselves in our conscious reasoning.

Have you ever felt like you were stuck in a rut? Have you ever tried breaking a bad habit? Even when you make a conscious decision to break a bad habit or to form a new habit, the effort required to do it is herculean.

We may blame our ruts on things like depression and the habits we cannot break on things like addiction. Maybe those gut level assumptions that form ways of thinking at a subconscious level are reinforced by our actions that align with them. Having committed (or not committed) to certain actions with the force of these subconscious influences, we employ our rational minds to defend our posture. Thus, the actions we take on impulse carry more weight and gravity in the way we think and reason than we realize.

Like a large ship in the ocean, we do not just turn on a dime. When our lives and the ways we act and think take direction, changing course is not as easy as we think it should be.

John the Baptist came, to prepare the way for Jesus, calling people to “repent, for the kingdom of heaven is near”. To repent means to turn around, to change direction from where you are going.

The religious leaders did not do that. They didn’t repent. They didn’t change direction and get baptized. They continued on the same path they were going. They continued to use their reason to defend their position resulting from their predispositions, and they missed God who became flesh and stood among them

Jesus called this being “born again”. Being born again requires repentance. This suggests some intentionality. It suggests that being born again is not something that happens reactively or reflexively; it requires stopping, considering, and changing direction. It might even require a conscious decision.

I will end my thoughts today with CS Lewis, who had a keen sense for the workings of human motivation and behavior that he worked out in poetic prose in the Chronicles of Narnia, the Screwtape Letters, the Great Divorce, and other books. He suggests that people are never static in relation to God.

According to Lewis, a person is always moving in some direction in relation to God: you are either moving toward God or away from Him.

We tend to think about the pivotal times in our lives and the pivotal decisions we make. Lewis suggests, however, that the direction we are moving at any given time is governed by every little “decision” we make, consciously and (perhaps, more importantly) subconsciously.

Those gut level assumptions become habits of thought that drive our reactions and our actions. We do things sometimes just because we have always done them that way, and those actions may govern our beliefs more than we realize.

Thousands of thoughts and actions that we take in our daily lives provide inertia that influences our conscious decision-making. We may think that we are making a considered and reasoned decision without ever realizing that our considerations and reasoning are influenced by all the many gut level assumptions and impulsive actions we have taken before that decision is made.

The Pharisees & Sadducees knew the Scriptures, but they didn’t react to John the Baptist’s call to be baptized because they were predisposed not to react to it. They were predisposed to assume that they should not listen to or carefully consider anyone who did not rise up from within their official ranks. Because they did not respond to the call to be baptized, they were predisposed to not accept Jesus. And so they rejected God’s very purpose for themselves.

Postscript:

After having written this piece, I listened to a conversation with Abigail Favale on the podcast, Truth Over Tribe. (Christian Deconstruction: What I Wish I’d Known with Abigail Favale) She was raised evangelical, but she gradually moved away from Evangelicalism and Christianity as she embraced modern academics.

In the process of embracing modern intellectualism, Favale learned to critique the Bible and Christianity through a critical, suspicious lens. At one point in her journey, however, she became more curious. Looking back, she says that everything changed for her when she stopped being suspicious and started seeking to know.

She observed that the posture of her heart changed, but she also began to reengage in “Christian” actions, such as prayer, reading the Bible to understand, and going to church again. She says, “It was only when I entered back into the practice of Christianity that my intellectual conversion followed.”

The posture of our heart matters, and our practices matter as well.