“The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.” Albert Einstein

I am intrigued by the stories of peoples’ journeys, especially of their thought journeys. Some are more intriguing than others. The story of Pat Flynn fits squarely into the more intriguing category. (See the Side B Stories Podcast – Episode 78 – Science, Philosophy, and Reality – Pat Flynn’s Story)

Patrick Flynn has an educational background in philosophy. He embraced naturalism at an early age, but he encountered philosophical problems with naturalism when he read people like HL Menken and Frederick Nietzsche. These problems led him to seek answers that might provide a more coherent view of reality.

I am not going to try to summarize his whole story. You can listen to him describe his thought journey at the link in the first paragraph. I just want to focus on one aspect of his journey from atheism to theism.

Flynn’s journey took him from atheism to theism through the medium of philosophy. This process was intellectual for him, and not experiential. He became convinced of theism, first, before he even told his spouse, because he knew she was not particularly fond of religion.

He didn’t dive into Christianity after he became convinced of theism. He explored Eastern religions, first, perhaps because he had a good friend who was Indian. When the Eastern religions didn’t solve the philosophical problems posed by naturalism, he reluctantly began to explore Christianity.

One of the big issues Flynn had with atheism was the lack of explanation for the fact the universe is intelligible. Digging further, Patrick Flynn found that the fundamental, core commitments of science fit much better with theism than with atheism.

Flynn biggest problem with atheism was the fact that the world is intelligible. The intelligibility of the world didn’t make sense to him from an atheistic position, and he discovered that the intelligibility of the world makes more sense on a theistic worldview. Flynn now finds that his coherent questions, which are met with coherent answers, suggests intelligent input.

In my own thinking, I have often wondered about the sense in the assertion that inert matter has the capacity to create the intelligence we enjoy as human beings. How does such inert non-intelligent, non-conscious material living, conscious and intelligent? How do the elements in the periodic table develop the intelligence to create a periodic table? How does dust develop the conscious agency to sweep itself under a rug?

Intuitively, it doesn’t make sense to me. At least, when a magician pulls a rabbit out of a hat, there is a real rabbit (and an intelligent magician capable of exploiting peoples’ expectations). Rocks don’t become rabbits (or magicians.)

If we accept the principle that the world is intelligible, says Flynn, we are accepting a pretty powerful argument for the existence of God. Indeed, Christians advanced science precisely because they expected the world to be intelligible, and they expected the world to be intelligible because they believed it was created by a God who is intelligent (and intelligible).

The Greeks reasoned from intelligibility to abstract, impersonal ideals. Christian thinkers reasoned from a personal God to intelligibility. The understanding by Christians that an intelligent God created the world led them to expect that the world could be understood (even when it appeared haphazard and unintelligible). This understanding informed and fueled their scientific endeavor and laid the foundation for modern science.

The fact that the world is intelligible drives scientific enterprise, observes Flynn. Indeed, we could not do science without an intelligible world.

Flynn also observes that scientific method is replete with moralistic principles. Scientific method is built on integrity, honesty in reporting, commitment to follow the evidence where it leads, etc. Flynn asks, “From what does the morality of science arise on a naturalistic worldview?”

If the world is just the product of random colocations of atoms and energy, from what source does scientific method arise? (And I would ask, why does it matter?)

Flynn says that science, in a broad sense, is based on a kind of essentialism – the idea that things have common natures. Things we see in nature hold true in an essential kind of way that we can confidently apply when exploring other things that we know less or even nothing about.

We might call this “order”. Such order is something that we would expect on a theistic worldview. Flynn calls them “brute absurdities” on a naturalistic worldview.

Flynn says that a naturalistic worldview, at its core, is governed by a principle of indifference (which is blind and pitiless according to Richard Dawkins). “What can you expect to result from a driving principle of indifference?” Flynn asks. The answer, he says, is “Nothing!”

Flynn says that we should not expect order or intelligibility on a naturalistic worldview. Flynn finds, as do I, that theism makes more sense of the order and intelligibility we see in nature than naturalism does.

For instance, we see themes in nature. Charles Darwin famously picked up on those themes and conceived of the theory of evolution – natural selection acting on random mutations – to explain it. He did this because he was looking for an alternative explanation to God.

Darwin saw similar body “designs” from species to species. On a naturalistic worldview, that excludes God as a player in that “design”. Darwin supposed that “natural selection” could be the “actor” on random mutations, rather than God, to explain how similar designs evolved within species and from species to species.

His theory was brilliant, and it seemed to play out in the variations in finches’ beaks and animals isolated in their environments from other animals of the same species. But, does evolutionary theory adequately account for the origin of life itself? (Not yet) Or speciation? (Not very well) (See, Darwin’s Doubt, by Stephen C. Meyer)

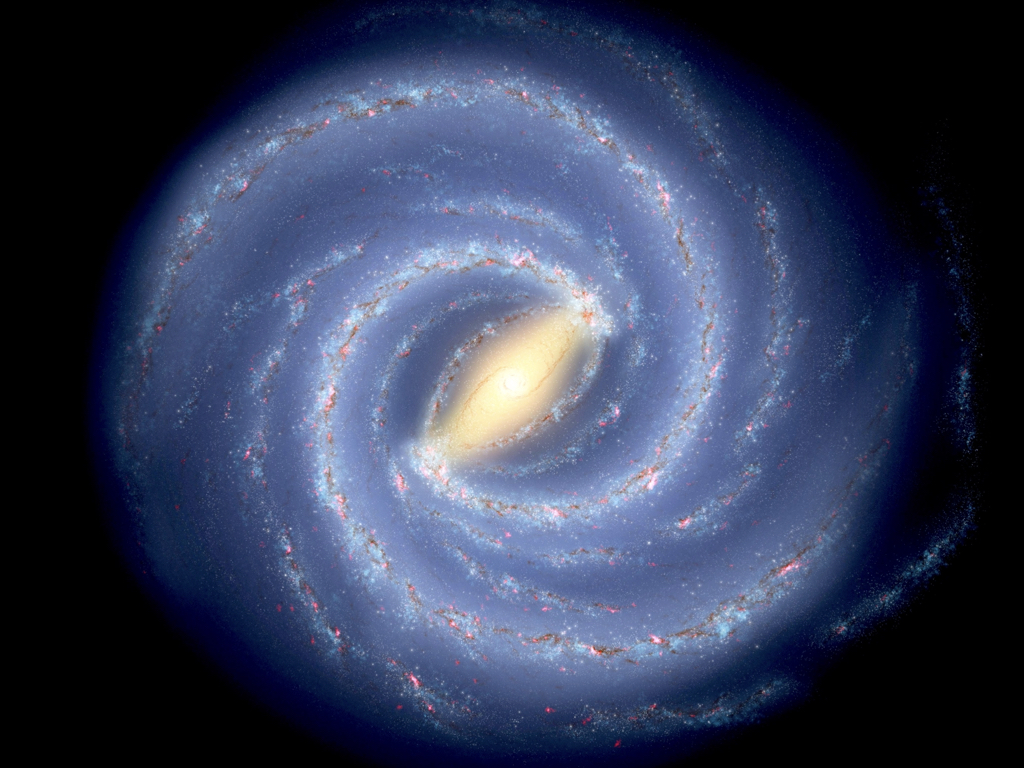

While evolution might account for similarities in life forms, it doesn’t begin to account for similarity in designs that we find in non-life forms. The Fibonacci sequence, for instance, is a design we find throughout various forms of living and nonliving matter in the universe from plants, to galaxies, to cloud formations, to musical sequences, etc. These design similarities shared by life forms and non-life forms, alike, defy explanation on evolutionary theory (and on naturalism as well. (See my thoughts on this in The Fibonacci Sequence: Common Descent or Common Design?)

We can plausibly proffer a theory like evolution to explain the phenomenon of the Fibonacci sequence in life forms that are organic and dynamic, but evolution has no explanatory power to account for the same design in non-life forms that are inert and have no self-replicating mechanisms. The evolutionary paradigm cannot account for the prevalence of the Fibonacci sequence in both living and non-living things.

These similar designs, however, are easily explained by the creative work of an intelligent God who uses similar designs throughout His creation.

I don’t want to be flippant about this or appear to lean on a God-of-the-gaps artifice as “proof” of the existence of God. I am merely talking about explanatory power and “elegance” in the explanation, which is the last thread in the strand that I want to tease out a little bit.

The principle of “elegance” and simplicity is preferred in our modern, scientific explanatory theses. Flynn asserts that non-theists are required to complicate their analysis in order to account for the data to maintain a naturalistic worldview. Flynn finds naturalistic explanations to be strained, complex and lacking in the “elegance” that is claimed as an important factor by people like Richard Dawkins.

Richard of Dawkins is fond of saying that he prefers simple and elegant explanations. On that point he assumes that God complicates explanations for what we see in the natural world.

If you listen to Dawkins long enough, you find that this is just a brute assertion. He assumes that naturalism, generally (and evolution, specifically) simplifies the explanation for what we see in nature, but he really offers no explanation why that is true. His attempts to expound on that point seem particularly contrived to me.

Elegance may be in the eye of the beholder, but simplicity is more measurable. Perhaps, we should ask our children which is easier to grasp. We might ask our children what makes more intuitive sense to test these assumptions.

Are children more likely to understand that evolution accounts for the origin of life and of the development of species? Or are children more likely to understand that God created life and the world we see?

We don’t really have to speculate on the answer. Children around the world in all cultures and religious traditions intuitively believe in a creator of the natural world. Experts even give this phenomena a name: universal design intuition.

Despite Richard Dawkins’ assertion to the contrary, the theory of a divine creator of the world is simpler and easier and more intuitive to grasp than evolutionary theory and naturalism. It also has much more explanatory power for such things as the universal prevalence of the Fibonacci design in wildly dissimilar types of things that we find in nature, including living and non-living forms (including non-physical forms like music).

Flynn finds naturalism and the analyses needed to support naturalism more complicated than theism and theistic principles. On that score, he says, “The more complicated the analysis, the more likely it is to turn out false.”

Again, I don’t want to make light of these things. Darwin found philosophy and metaphysical reasoning to be a “muddle”. He probably would agree with Dawkins that science and evolutionary theory is easier (for him) to understand than theology.

Science is easy in the sense that we can test things, and they will prove out (or they won’t). The math works, or it doesn’t. Gravity works the way gravity works whether we robustly understand how it works, or not.

But the raw science is never the end of the story. We leave science pretty quickly when we stop simply looking at the data, and we start drawing conclusions from the data. For instance, I heard Neil de Grasse Tyson make the following statement: science is the study of all of reality; therefore, we don’t need philosophy because we have science.

Tyson failed to grasp that, in making that statement, he made a philosophical assertion and not a scientific one. The claim that science tells everything there is not know about reality is not provable, and it is not falsifiable like a claim that a force like gravity exists. The conclusion that science has replaced the need for philosophy is, itself, a philosophical statement!

How does Tyson know that no reality exists other than what science can prove? What objective test can he run that will demonstrate the claim? What scientific proof does he have to show his thesis is true? What possible scientific proof could he have??

I dare say, “None!” But that’s because science is limited in its scope. Science is the study is limited by definition to the study of the natural world. How, then, can science prove that no reality other than what we find in the natural world exists?

Tyson and other people like him who want to exclude all inquires but scientific ones are counting on science to prove more than what it is designed to prove or capable of proving.

Another example is Darwin, himself. He eventually rejected his own intuition that purpose (and God) exists in the world on the basis of his reasoning. He reasoned that he should not trust his intuition because his intuition developed from lower life forms. Therefore, he concluded, “Who could trust the intuition of a monkey’s mind?” (My paraphrase)

Again, Darwin was not educated in religion or philosophy, which is perhaps why his thinking was so muddled about it. Like Tyson, he failed to appreciate the philosophical implications of his own reasoning: if he developed from lower life forms, then on what basis should he trust his own reasoning ability? After all, we might ask, “Who could trust the reasoning of a monkey’s mind?”

I agree with Patrick Flynn that the intelligibility of the world is a problem for naturalism that requires philosophical acrobatics to arrive at the desired conclusions (and those acrobatics often result in absurd twists and turns). The intelligence baked into the world is easily (and elegantly) explained by an intelligent Creator.

The origin of life deriving from inert, inanimate, and lifeless matter requires contorted mental gymnastics, while the origin of life is exactly what we would expect from a living Creator. The fact that the universe is highly ordered is no surprise if it was created by an intelligent being, but it defies good explanation on a theory that relies on random chance. The intelligibility of the universe is not a problem for the theist, but it poses some significant challenges for an atheist constrained to a naturalistic worldview.

Postscript:

If you like stories as much as I do, you should check out the Side B Podcast where Jana Harmon interviews former atheists who have jettisoned their former worldview for a theistic worldview. Walking with them back over their journeys is intriguing and informative.

Good article Kevin 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Tom!

LikeLike

Your observations about the limitations of science and the importance of philosophy in understanding the nature of reality are particularly insightful. Science, by its very definition, explores the natural world, but it cannot address the broader questions about the purpose and meaning of existence. These questions often lead us into the realm of philosophy, where our beliefs and worldviews are constructed and explored. Your example involving Neil de Grasse Tyson underscores the critical role of philosophy in shaping our interpretations of scientific findings.

Your discussion of the challenges faced by naturalism, particularly in explaining the origin of life and the ordered nature of the universe, offers a compelling argument for theistic worldviews. The intricacies of life and the remarkable order of the cosmos indeed appear to be more elegantly explained by the existence of an intelligent Creator. The theological perspective finds strength in these observations, as it aligns with the belief that the universe’s design reflects divine wisdom.

LikeLiked by 1 person