Certain “aha moments” stick with me and are a continual point of reference in my life. Many of them happened, not unsurprisingly, when I was in college – a time when I was searching and open to learning.

For some background, I went to a small liberal arts college where a premium was attached to reading and writing. Philosophical discussions were not uncommon over food and drink. Professors would commonly gather in spirited debate in the one (and only) fast food joint on the campus as the students. I loved the academic atmosphere.

One ongoing debate among students was who was the smartest professor on campus. The debate came to an end one day when one of the favorites (a professor who taught Latin, Greek and Logic) took his own life one night. The scuttlebutt was that he came to the dire conclusion that God does not exist, and he ended his life.

The other professor who was most often championed as “smartest” when was one of the two religion professors on campus. He was enamored with Liberation Theology (the thought that God was maturing and changing with His creation, among other things) and otherwise had an “all roads lead to the top of the same mountain” view on religion.

His counterpart was Jewish. At the same time, one of the more popular professors (among the intelligentsia on campus) was an undeniable guru of Western Civilization. His Western Civilization classes were staples of the curriculum. Though there was plenty of partying and “normal” college life, my college was a cloistered incubator of discovery for anyone eager to learn.

The Western Civ prof (harkening back to college speak) gave a popular series of lectures in the evening (popular, at least, for the people more interested in political parties than dorm parties). These lectures were voluntary, but well attended. His lectures featured the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas and the connection between science and faith.

His lectures were popular, I believe, because they propped up faith for the “smart” college student who grew up believing in God who was suddenly facing the disdain of the academic community. The overwhelmingly predominant worldview on college campuses in those days, and more so now, is anything but a worldview with God as the central figure.

This professor reasoned in these lectures that empirical, scientific evidence, reason and logic leads a person inevitably up to the steps of heaven to the door of faith. (The metaphor is mine.) He was arguing against the notion that faith requires a “leap” – a disconnect from the more “objective” grounding of science, reason, and logic.

I wondered, then, whether he was right. My intuition suggested otherwise, but I didn’t know quite why. I have been thinking about his premise ever since, and I have a better grasp on the reasons why I believe his premise isn’t true than I did in college.

Modern Western thought driven by a commitment to empirical evidence – things that we can touch, see, feel and hear and, therefore, know through our interaction with the material world. We are steeped in the scientific method, and science is the darling of our modern thinking.

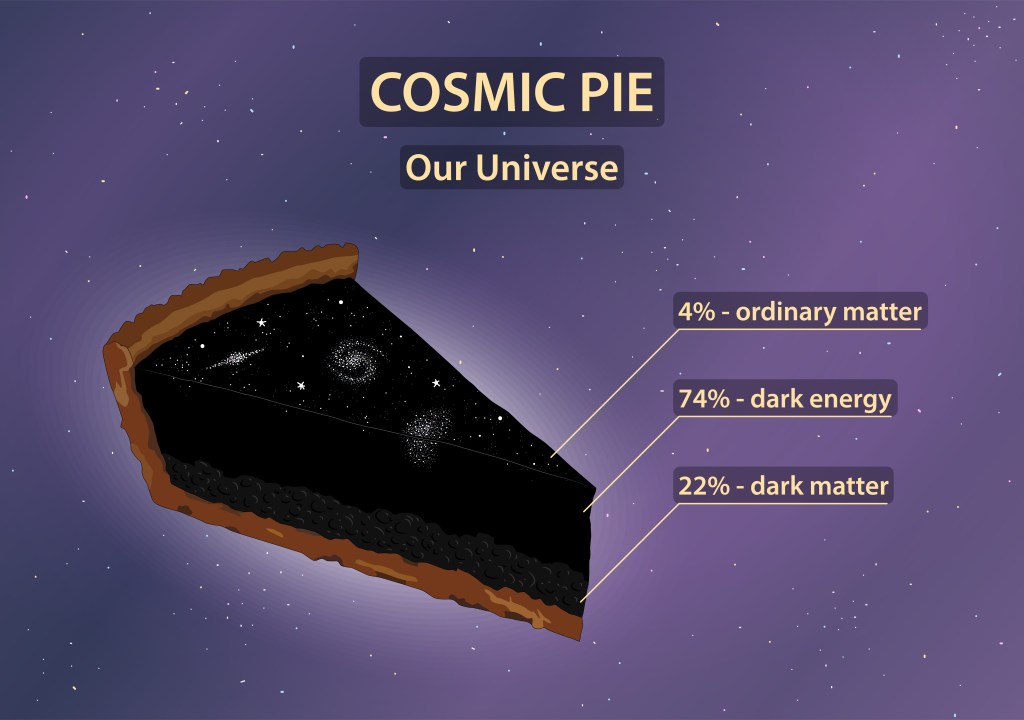

With the most powerful telescopes humans can devise, however, we cannot see to the end of the universe. Most of the observable universe (what we can see) is comprised of dark matter and dark energy, and we don’t even know what they are.

With the most powerful microscopes, we cannot see the smallest of matter. The world extends beyond our reach and our ability to know in all directions.

We are like children groping in a vast, dark room discovering and piecing things together the best that we can. Dimensions may even exist of which we have little or no knowledge, dimensions that we cannot see, feel, hear or touch and have difficulty even imagining.

(I wrote this in 2012, before I discovered Hugh Ross and Reasons to Believe. RTB is an organization that seeks to harmonize science and faith. The founder, Hugh Ross, is an astrophysicist by education and profession, wrote The Fingerprint of God in which he describes 10 dimensions, though we can’t really grasp more than four, and we can experience only three.

Another popular path favored by academicians is logic. Again, I have always been skeptical that logic is the path to God (or any kind of certainty for that matter), but I couldn’t always articulate why.

My skepticism stems from the necessity of a starting premise. If the premise is flawed, the conclusion will miss the mark. My skepticism flows from the fact that human beings are finite. How are we to know the right place to start our syllogisms?

In my short 50+ years of life (60+ now), it seems to me that people usually start the syllogism in a place that is pointing toward the conclusion they believe will be reached (or want to reach). We are flawed that way, led usually by our own biases and conclusion we have already reached. (This is the premise of Jonathan Haidt’s brilliant book, The Righteous Mind.)

That does not mean that disciplined thinking has no place in the conversation or that we should dismiss or ignore what we know. It merely means that we should be mindful of what we do not know and open to realities we do not currently grasp.

I have always thought that faith is a leap, but now I see that all our ultimate conclusions are leaps. We have gaps in our knowledge, and we always will. That is the reality of finite beings who don’t know, and probably never will know, all there is to know.

We live for maybe eight decades. Then we die. What can we really know of an infinite universe that has no visible beginning or ending? Let alone regions and dimensions that we cannot see.

I also firmly believe that every single person in the world, religious, agnostic or atheist lives by faith. Faith comes with being finite. It is the inescapable consequence of finiteness.

We have all leap to our own conclusions. We cannot and we never will see the end game, at least in our current state. How we interpret the world, therefore, is necessarily a leap of faith.

The theist lives by faith that God exists. The atheist lives by faith that no God exists. Both positions are chosen by people based on what they know and how they interpret what they know.

In western civilization, we take comfort in what we know. We measure, analyze, and categorize it. The earth rotates around the sun in the same direction. Gravity causes things to fall when suspended in air. We can use what we know to predict things like the appearance of comets in the sky with a great deal of accuracy.

At the same, we (human beings) have only been around for a very, very short time in the scheme of things. No individual human lives very long at all. Each one of us is barely a mist in the vastness of time and space.

I have always thought we have a certain unseemly arrogance embedded into our western thinking. Who are we to be so certain given the undeniable finiteness of our existence? As clever as we have been to learn so many things about the universe, given our fragile and fleeting place in it, we do not know what we do not know.

So this all leads me to that “aha moment.” In a class from the Jewish professor in which we were studying the books of the Old Testament, he came in one day with a change of direction. He began with the statement that the Jewish religion is more eastern than western in origin.

To illustrate the difference, he asked the class to consider the world as a chair in a room. He described that the western man would begin to examine the empirical evidence, measuring the dimensions of the chair, the distance of the chair from the walls and ceiling, and the dimensions of the walls and ceiling. The eastern man would begin with the question: “How did the chair get here?”

That illustration has always stuck with me. We live in a materialistic world, as the song goes. We easily forget our place in the world, such as it is, and focus on what we see in front of us, as if that were all there is. Even our greatest scientists, physicists and thinkers have the same tendency. We scour what we see, giving little thought, or not wanting to think, about what might lie behind, before, above and beyond it all.

How is it that we trust our own judgment so much? Considering that we are less than a bump on a pimple on the universe. In the end, there is nothing but faith.

For some extra-curricular reading, try KANT’S RELIGIOUS ARGUMENT FOR THE EXISTENCE OF GOD: THE ULTIMATE DEPENDENCE OF HUMAN DESTINY ON DIVINE ASSISTANCE by Stephen R. Palmquist (“achieving certain knowledge of God’s existence transcends the capabilities of human reason”).

One thought on “Leaps of Faith”