I have heard a number of people assert that Christianity gave birth to the scientific method. Perhaps, the first time I heard that claim was from John Lennox, the famous Oxford University professor of mathematics. I was intrigued, but I didn’t take the time to research his claim at the time.

I have heard the claim repeated multiple times, most recently by Dr. Michael Guillen the astrophysicist, former Harvard professor and TV personality. In fact, he devoted a podcast to the subject (embedded below), so I figured it was time to learn more.

I started with Wikipedia, which has a page on scientific method. Wikipedia begins with Aristotle and focuses on rationalism as the basis for scientific method.

Properly speaking, rationalism is not a method. It is a philosophy, a way to approach the world. Rationalism and Aristotle, though, seem to have led the way to the development of the scientific method.

Aristotle’s inductive-deductive method that depended on axiomatic truths and the “self-evident concepts” developed by Epicurus was an early conception of the way to do science. It was jettisoned, however, for something more like the modern scientific method beginning around the 16th Century. Perhaps, this is why Guillen doesn’t mention Aristotle, except in passing.

After those early pioneers, Wikipedia references some great Muslim thinkers who were influenced by Aristotle (including Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and Averroes (Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad Ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rušd)). They placed “greater emphasis on combining theory with practice”, focusing on “the use of experiment as a source of knowledge”. Guillen starts his history of scientific method with these early “flashes” of scientific method in the Muslim world.

These men of the Islamic Golden Age pioneered a form of scientific method, but the inertia did not continue. Moses ben Maimon (Maimonides), the great Jewish theologian, physician, and astronomer, developed a similar emphasis on evidence. He urged “that man should believe only what can be supported either by rational proof, by the evidence of the senses, or by trustworthy authority”. He foreshadowed a future scientific posture, but his prescience also did compel further advancement at the time.

Dr. Guillen credits Robert Grosseteste and Roger Bacon with the formation of the first actual principles of scientific method. Their ideas “caught fire” in Christian Europe from the tinder of academies that began just after the turn of the first millennium, igniting a blaze that would fuel scientific inquiry and endeavor for centuries to come.

“Concluding from particular observations into a universal law, and then back again, from universal laws to prediction of particulars”, Grosseteste emphasized confirmation “through experimentation to verify the principles” in both directions.

Roger Bacon, Grosseteste’s pupil, “described a repeating cycle of observation, hypothesis, experimentation, and a need for independent verification”, including the recording of the way experiments were conducted in precise detail so that outcomes could be replicated independently by others. Bacon’s methodology lead to the modern emphasis on peer-review in science, says Guillen.

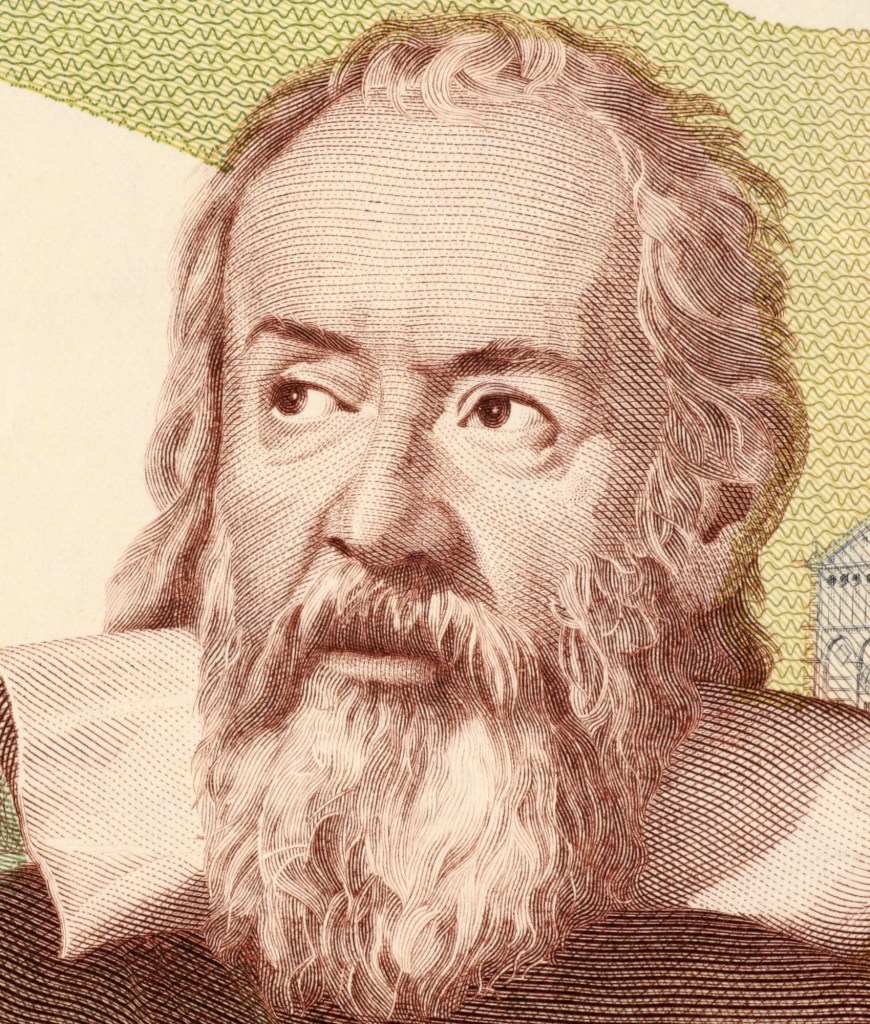

Wikipedia mentions Francis Bacon and Descartes. Bacon and Descartes emphasized the importance of skepticism and rigid experimentation, expressly rejecting Aristotle’s dependence on first principles (axioms). Guillen, however, glosses over Descartes to get to Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton.

Galileo Galilei introduced mathematical proof into the process and continued to distance science from reliance on Aristotelean first principles. Galileo and Newton reformulated the terms of scientific method that would inform modern scientists ever afterward.

That the two latter men were men of faith, along with Grosseteste (a Catholic Bishop) and Roger Bacon, his student, is significant. Maimonides and the Islamic thinkers before him were also men of faith. These men who pioneered the way to modern science were all monotheists who believed in a creator God.

Science did not really take off until the 17th Century. The trailblazers of the modern scientific method were religious men, and the modern scientific method was born in the religious environment in Christian Europe lead, primarily, by men of faith.

Why did science catch fire in Christian Europe and not in other parts of the world? Why not in China? Or in the world of the eastern religions? This is a question Guillen poses, and he provides a possible answer.

Dr. Michael Guillen says that the scientific method took off in Christian Europe because science and Christianity are “soulmates”, and “they agree on all the fundamental truths of reality”. This is a bold claim, especially in an age in which popular opinion seems to assume that science and religion (and Christianity in particular) are fundamentally opposed to each other.

Nothing could be further from the truth, Guillen says. He points to the the modern conception of time as an example. He says the Bible and science agree on the character of time – that time is linear, and not cyclical. The biblical assumption of linear time is one reason why science flourished in Judeo-Christian soil.

Monotheist tradition (including Islam) holds to the linear concept of time is linear which forms the basis of physics. Dr. Guillen is no novice when it comes to science, and the subject of time is one area of his expertise, having taught a course on time at Cornell University.

Eastern religions view time as eternal supported, which is the basis for concepts like karma and reincarnation. The Greek thinkers, like Aristotle, also believed that time is eternal and cyclic. In fact, Aristotle, believed that history and opinions repeat repeat themselves in infinite cycles.

People of any religion can be scientific, but the idea that time is eternal and cyclic is incompatible with modern science. Science demonstrates that time is linear and not eternal. Because Judeo-Christian Scripture (and the Koran) harmonize with that concept of time, it makes sense that modern science developed out of monotheist thought.

The first verse in the first chapter in the first “book” of the Bible states, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” (Gen. 1:1) The idea of a beginning is the essence of a linear view on time. Hugh Ross, another astrophysicist who is a theist, recently wrote on the distinction between Christianity and eastern religions, saying:

“Man is destined to die once, and after that to face judgment. Other relevant Bible passages are 2 Samuel 12:23, Ecclesiastes 12:5, Daniel 12:2, 2 Corinthians 5:10.”

The Christian concepts of a beginning, one life, death, judgment and even resurrection assume linear time, not cyclic time. It turns out that science corresponds to these concepts that are found in the Abrahamic religious traditions.

Unlike other religions, Christianity conceives of God as personal Being. The idea of God as uniquely personal also makes a difference. Because of that belief, Christians view science as more than a discipline; “It is something deeply personal,” says Guillen. It provides the motivation for men of science to want to explore the world made by a highly personal God with a religious fervor.

Guillen says of himself that he loved science before he became a Christian, and the pursuit of science consumed his life. He described himself as a “scientific monk”, because Science was all he thought about. After becoming a Christian, however, his motivation to do science became richer and deeper.

Thus, Guillen recognizes that people can obtain joy and satisfaction from science without believing in God and without being a Christian. He speaks from experience on that score.

He also speaks from experience when he says that doing science as a Christian is different. It is more “deeply personal”. The deep, personal connection with science grows out of relationship with God and a desire to know the mind of the creator of the universe.

If you want to hear Dr. Guillen wax on about these things, his podcast episodes brim with that sense of deep, personal connection between science and God. Thus he, submits that a reason science “caught fire” in Europe is because men of faith who were steeped in Christianity, viewed time correctly and pursued science with devotion to God.

Ironically, a neo-rationalist movement away from faith began around the same time modern science was developing. Men like Descartes and Bacon came out of the Christian tradition but, they began to pull in a different direction.

We call that direction the Enlightenment. Over time, the Enlightenment resulted in a kind of divorce between science and faith. This is the narrative recited by influencers who, more or less, attempted to wrestle science away from the Church. That narrative has carried forward to the current time. Thus, people popularly believe today that science and faith are opposed to each other.

The Enlightenment spawned a competing worldview and competing philosophy, and many people who do science have adopted that philosophy and worldview. The Enlightenment mantra, that the Church held back science and the advancement of man, however, is a myth. I have written about it a number of times, including in the context of Tom Holland’s book, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World.

A large segment of the Church backed away from science since the Enlightenment period because they, too, bought into that tension narrative. But not completely. In fact, the second half of the 20th Century saw a tension begin to grow within the Church, itself, pulling in opposite directions, and the 21st Century has seen a resurgence of interest in science by people of faith.

Science, itself, has greatly influenced this resurgence. For men like Dr. Guillen, science was the path that led him to the Christian faith. Other scientists, like Hugh Ross, Sy Garte, Fuzale Rana, and many others tell similar stories about the way that science led them to question their materialistic, naturalistic and physicalist assumptions and set them on a journey that ended in faith in God.

Some of the greatest scientists in our day, like James Tour and Francis Collins, just to name a couple, are men of devout faith. “Scientific method is not the enemy of Christianity”, says Dr. Guillen, with good reason.

Indeed, it is not. Christianity was the fertile soil in which scientific method and modern science began to grow strong on a foundation set in place by men of faith, and that foundation continues today.

A person need not believe in God to do science any more than a person needs to know the painter to study and appreciate a painting. Knowing the creator/Creator, however, makes the study a deeper and more personal undertaking.

Roger Bacon and Nicholas of Cusa are two of the important writers/thinkers who led to the scientific method of observation and experimentation as opposed to creating a “thought experiment” which remains internally consistent but may not match the real world. Probably no group of individuals should be credited with the development of science, though; it’s been a process, built in an environment of asking questions and seeking answers, which flourished in Christian Europe in the centuries before the Enlightenment, at which time science and philosophy parted ways and followed different paths. J.

LikeLiked by 1 person